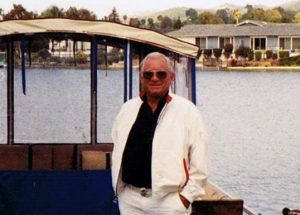

Jack Minde

November 28, 1928 – March 15, 2010

I love my father. That’s the first, most important thing.

Thank you all so much for your concern and your compassion. Thanks don’t suffice to express the sense of comfort my family and I feel in this terrible time, mourning the loss of my father Jack Minde.

He was the kind of man I could still call “Daddy” at the age of 50 without feeling embarrassed. For those of you who did not know him—and for those of you who did—I can only say that my father was a quiet hero of the most honest kind. If he could hear me say that, he’d tell me I’m being ridiculous and to shut up. He never asked for praise; he merely did what needed to be done, whether it was going to work every day and earning a living or being drafted and sent to Korea. He never won any showy medals. He was a good soldier, a pfc, and he never accepted another stripe even when it was offered to him. He faced frontline combat, but he never told any war stories afterward. “Don’t be a bull—-ter,” he’d tell me. It’s a lesson I’m still learning.

At an age when most of us are still children, my father lost his parents and siblings at Dachau. At twelve he was in the Kovno Ghetto. At fifteen, he was a slave laborer, building a German airfield. At seventeen, he was in a Displaced Persons Camp. He came to this country on New Year’s Day 1947. The most wondrous thing is that, despite what he had lived through, he was able to have the most ordinary of lives. He married my mother. He raised me. He raised Stacey. He built us a happy home. He loved us. He was able to do all that simply because he had an indomitable spirit. Even in his last days he fought to stay alive. And he almost succeeded. There was just too much happening to him, too fast, at the age of 81.

And he laughed. If you knew my father, you knew that he had a playful sense of humor. It wasn’t always evident on the surface. But it was always there. Daddy once took me for a new suit in the “Portly” department. I never knew if he was joking when he called it “Porky.”

He developed gout. He called it “Alter buck” The Old Goat, in Yiddish. Somehow, I became The Old Goat, and to his last moments he would smile when I’d tell him, “The Old Goat is here!”

He wasn’t outwardly affectionate—that’s Mom’s job—but he was compassionate. He often told me that he had known what it was like to be hungry, and that he didn’t like other people to know want. So he—very quietly—would buy a hamburger for a penniless hungry person, or invite someone to share what he had. The door was always open. My friend Gary, who I’ve known since childhood and who practically grew up in my house, called Dad his second father. We laughed at Gary’s recollection: “What? You’re here again? Here, have a slice of pizza!”

He once told me that he wouldn’t be here forever, all too true, and he once told me to take my car to a shop to have a new starter installed. That is, until he heard what it was going to cost: “No son of mine is going to pay that!” Dad stayed up all night in the garage, a single light burning like Dr. Frankenstein in his laboratory, and built a starter for my car from a part here, a part there. He could build or fix anything. He never got the hang of flying a kite, though.

Some of you know that I took the Buddhist Precepts some years ago. Daddy already had Alzheimer’s at that point, but he would ask me if I was still involved. He knew what it meant when a pressed my hands together, bowed, and mumbled. He’d smile. Sensei Doshin gave me the Dharma name of “Konrei,” the Unyielding Spirit, but the truth is, I learned it all from my Daddy.

What’s best in me comes from my Dad and Mom. As for what’s not best, well, I have a very high standard to live up to. I learned one thing this past week watching my Daddy die, and that is that we live but a moment. In that moment we have to love like forever. Eighty one years is nothing.

There’s so much more I need to learn from him, and so much more I wish I could say to him.

“Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

He did, right up to the end.

Sheila Minde

November 17, 1936 – March 15, 2017

Of course, I can’t talk about my Dad without talking about my Mom, for theirs was a love story that lasted most of their lives. My Mother was born in Brooklyn in 1936, the daughter of two Russian immigrants who met and married only after they’d both fled the Russian Revolution. The idea of America as the “Goldene Medina,” The Golden Land, was strong with my grandparents, and they passed their love for America as a land of justice and fairness and peace down to their children.

My Mom was the quintessential middle child, sometimes described as a “goody two-shoes” by her siblings, but she was never self-righteous. An animal lover and an advocate for animals, she was never happier than when she was with her Bichon Frise, Pepe, and I think she was proudest of me in my law career when I helped establish an animal rescue.

She met my Dad just after he’d returned from service in Korea. He was renting a room from her Aunt. The rest is quiet history. They met when she was just sixteen and married when she was only eighteen, and spent, in total, 57 years together. In all that time, I never saw the house disordered, and I remember only two arguments that made any impression on me because they were unusually forceful. I don’t even remember what they were about.

Not that it was necessarily a quiet house. They tended to talk to each other loudly, and they were not always in agreement, but they could finish each others’ sentences. My Mother’s father was a reader of newspapers (several, every day) and my Mom stayed up on the news. It was a good thing, because my Dad was also a news junkie. When they invented CNN we couldn’t pry him away from the TV. Both of them could argue current events for hours. I remember watching JFK’s funeral on our small black-and-white Admiral TV with my Mom while my Dad was at work. When the Apollo 1 astronauts died, she cried. When Dr. Martin Luther King was killed I can still recall the tone in her voice when she said, “What is happening in this country?” I remember my Mom screaming when Robert Kennedy was shot.

I remember my Mom laughing. A lot. She had one of those silent quaking laughs, the kind that shakes your entire body, and when she found something funny (or said something funny, as she frequently did), she would laugh until she was red-faced. Then she’d laugh some more.

She was a true “lady,” always polite and courteous and soft-spoken. I don’t think I ever heard her shout. She was a little self-conscious about her Brooklyn accent, and so she cultivated a public speaking voice in the Mid-Atlantic Accent favored by radio and TV announcers while she was growing up. As a kid I thought it was pretentious, but it was just her way of making sure store clerks, telephone operators, and my teachers understood her.

She loved history, particularly anything to do with the Victorian Age or gaslight New York. My Dad and I would groan whenever she announced she wanted to watch something: “Here come the long dresses and English accents again!”

Our home was an open house — everyone was welcome there, there was always food and companionship, and so we attracted a lot of strays — cats and people, mostly, who had no place else to go. She cooked in a very Old World / Eastern European fashion, and I grew up thinking heartburn was just the natural end result of a meal. “Eat it with bread!” she’d insist, whether it was a slice of cheese or a piece of steak. Keeping my weight down has been a lifelong challenge. Since she passed it’s been less of an issue. Sometimes you wish for a small trouble.

At the end of a workday she would sit by the window waiting for my Dad to drive up. He always did.

When he passed away in 2010, she soldiered on. Like my Dad, she was too strong just to let life get the better of her, but she was never the same; she was always sad, even when she didn’t seem to be.

A series of health problems dogged her in the years after Daddy left. She suffered pneumonia after a bad fall, and it nearly killed her. She had episodes of heart failure. She had DVTs. She developed breast cancer in 2015, fought her way past it, through a series of post-chemo hospitalizations, and received word that her treatment was ended just a week before she died suddenly and without any warning. She’d fought her last good fight and won, and it was time to be with “her Jackie.”

The day was March 15, 2017, seven years to the day after my father died. It’s not a coincidence.

Rebecca Hope Kraas

May 6, 1967 – April 8, 2013

Those of you who have worked with NSNN for any period of time remember Hope, our Program Coordinator. She was everywhere we needed her to be — answering phones, filing, sitting in on consultations to calm nervous clients, promoting our work tirelessly. She was a force of nature, always bright, always sunny, and always ready to fight like a lioness if she felt that someone was getting a raw deal. If she wasn’t formally educated in the law, she understood justice better than most people.

She was a very private person in many ways, so many of you never knew that her son Bronson had become paraplegic after an horrific car accident that nearly took his life and left him for a coma in weeks. (Bronson passed away a few months after Hope, so she was spared that wrenching sorrow.)

Few of you knew she suffered with Borderline and Bipolar disorders that she with struggled with for years. Her work kept her grounded, that and the people she loved. In the last two years of her life she was diagnosed with Polycythemia Vera, a rare blood disorder that usually affects people in their seventies and eighties. Since she was so young, the doctors tripped across her diagnosis by accident, and by that time the disease had progressed too far for effective treatment.

She died at the age of 45, still young, still beautiful, still funny, warm, and vibrant. Although we kept it out of the office, she and I had a twenty year long personal relationship. Her death left me bereft. And the office now is terribly quiet.