The Brooklyn Dodgers are one of the most storied and fabled teams in all of baseball history.

The Brooklyn Dodgers are one of the most storied and fabled teams in all of baseball history.

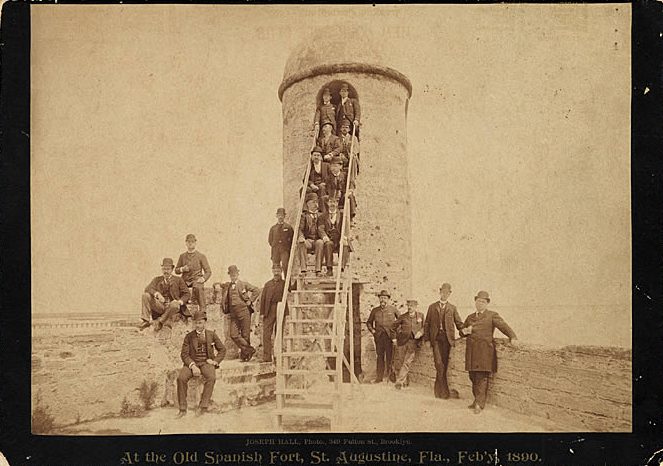

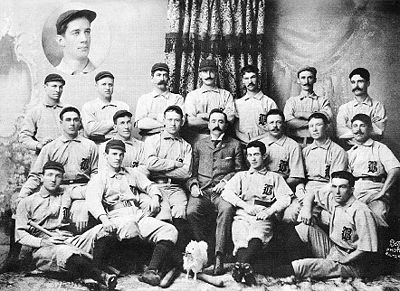

Officially named “The Brooklyn Base Ball Club, Inc.” throughout it’s history, the team that would become known as The Brooklyn Dodgers was established in 1883 and joined the American Association in 1884; they won the American Association Pennant in 1889 and joined the National League in 1890, where they remained. Winning the National League Pennant in 1890 makes the Dodgers the only team to win back-to-back Pennants in opposing leagues, ever.

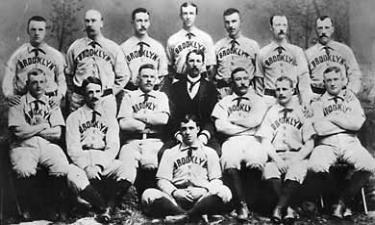

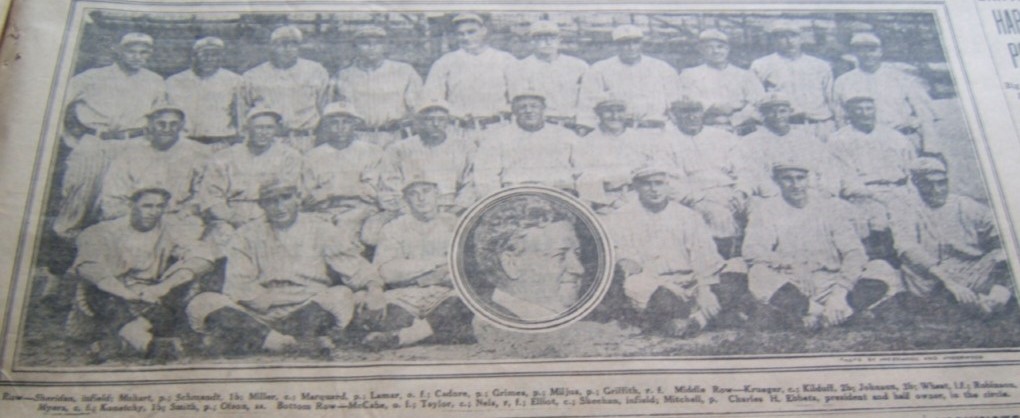

The 1890 Brooklyn “Superbas” after winning the NL Pennant

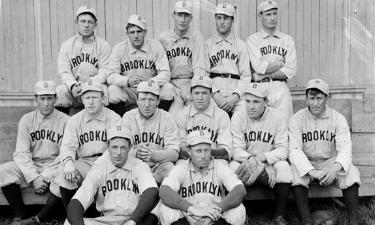

Team names were fluid in the early days, and were bestowed by sportswriters as a form of shorthand. Frequently, the same team was identified by different names even in the same news article. Teams themselves were just as fluid. The 1898 Baltimore Orioles were moved to Brooklyn en masse by their joint owners, becoming 1899’s Dodger lineup. (A sidelight: The Baltimore Orioles were reestablished under new ownership in 1901, and moved to New York in 1903, becoming first the Highlanders and then the New York Yankees! The current Baltimore Orioles are the former St. Louis Browns.) It is the Brooklyn Dodgers, however, who hold the distinction of having the most monikers.

The Brooklyn team was called by a variety of nicknames before the name “Dodgers” finally became exclusive, sometime as late as the 1930s. They were originally called the “Brooklyn Atlantics,” and then the “Brooklyn Grays.” New Yorkers took to calling them the “Brooklyn Bridegrooms” after many of the team’s players got married in quick succession. They earned the nickname “Trolley Dodgers” (or just “Dodgers”) during the 1890s, because fans and players had trouble accessing their home field, which was surrounded by a knot of busy trolley lines; it was said that fans and players literally had to “dodge the trolleys” while crossing the street to reach the ballpark. Managed by Ned Hanlon in the years 1899 to 1905, they were also nicknamed after a popular vaudeville revue of the era, “Hanlon’s Superbas.” It was as the “Superbas” that the team won its early Pennants and the Pennants of 1899 and 1900 as well

The 1898 Baltimore Orioles moved away from Maryland and became the Pennant-winning 1899 Superbas

The 1898 Baltimore Orioles moved away from Maryland and became the Pennant-winning 1899 Superbas

Besides “Dodgers,” all these names were used interchangeably by the press, along with the moniker, “The Brooks,” short for Brooklyn. The fans called them “Dem Bums” (when they played badly) or “Our Bums” (when they played well). Either way, the “Brooklyn Bums” became one of the most successful franchises in baseball history.

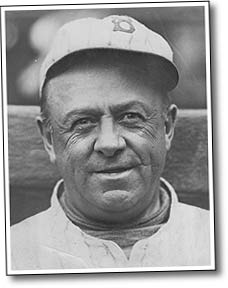

“Uncle Robbie: Like his hat, his Daffiness Boys were frequently cockeyed”

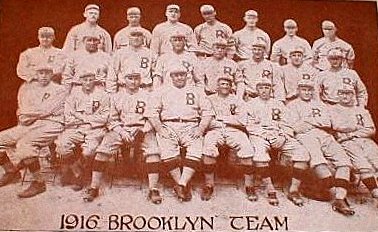

The team became known as the “Robins” in 1914, after manager Wilbert Robinson, who managed the team until 1931. “Uncle Robbie” led them to two Pennants in 1916 and 1920. But Uncle Robbie’s tenure was marked by continuous decline, mismanagement on the field, and acrimony between the team’s owners. Without meaningful leadership, the “Daffiness Boys” became the laughingstock of professional baseball, never rising above sixth place in the standings.

The “Robins” lost the Series to Babe Ruth’s Boston Red Sox

The “Robins” lost the Series to Babe Ruth’s Boston Red Sox

Early Dodger teams played in three ballparks, the trolley-choked Eastern Park and two incarnations of Washington Park. Team owner Charles Ebbets, dedicated to keeping the Dodgers in Brooklyn, decided to replace rickety Washington Park with a modern brick-and-mortar stadium. Ebbets quietly acquired parcels of land in the area then known as “Pigtown,” until he owned an entire block of lots. The new stadium, named for Ebbets, opened its gates on April 9, 1913. While Ebbets himself preferred to keep the name “Washington Park” for the new location, he was overruled by the other Dodgers stockholders who wanted to honor his efforts, but he did manage to avoid the proprietary-sounding “Ebbets’s Field,” as he modestly believed the field belonged to the fans, not to himself.

Charles Ebbets around the time he bought the Dodgers, and the home in built for them

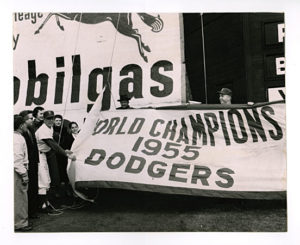

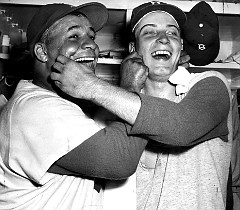

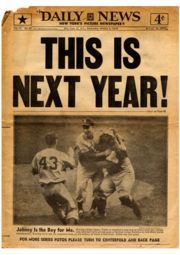

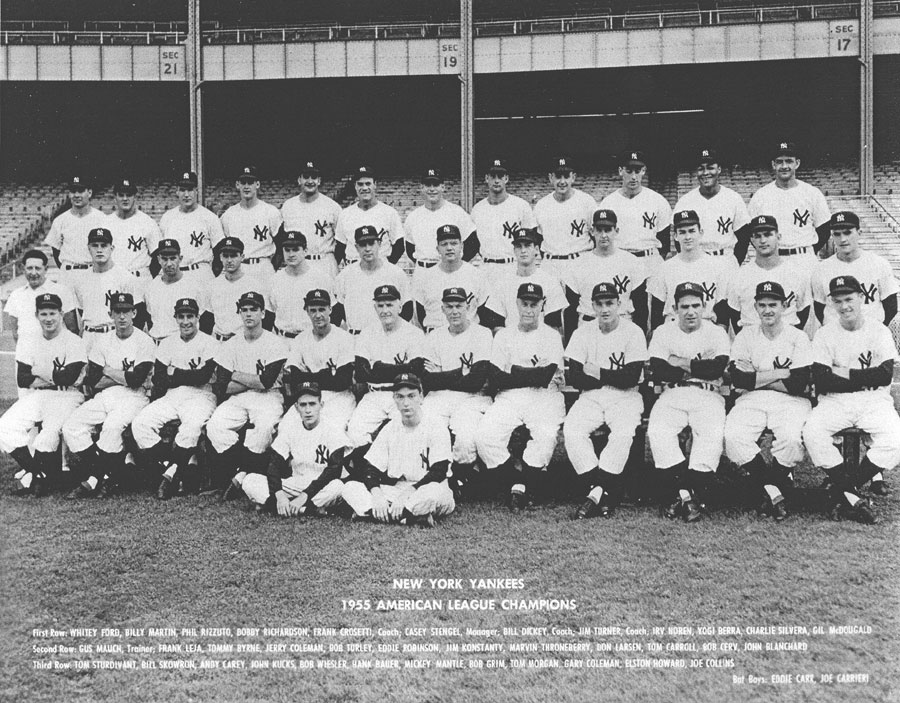

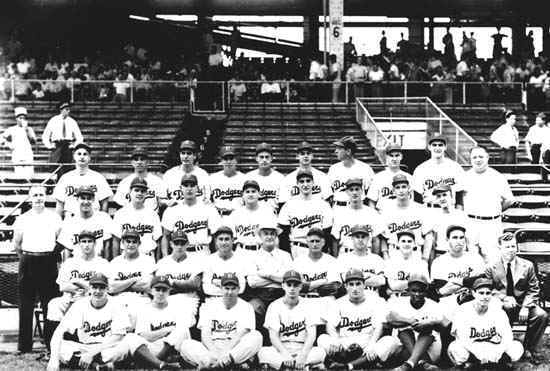

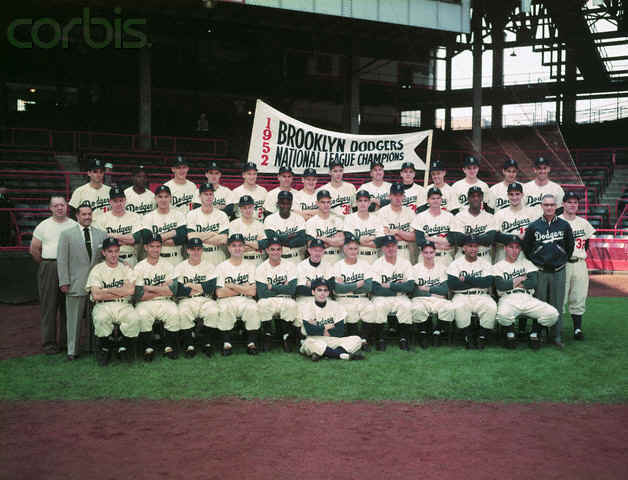

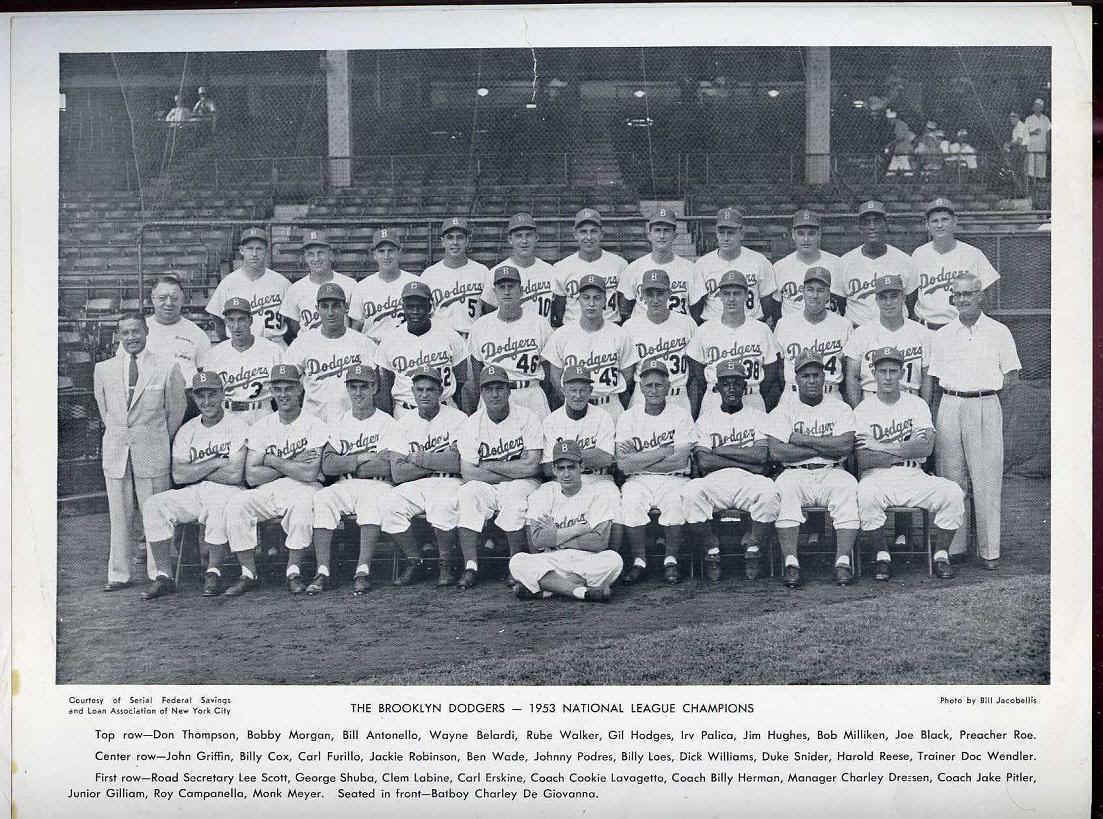

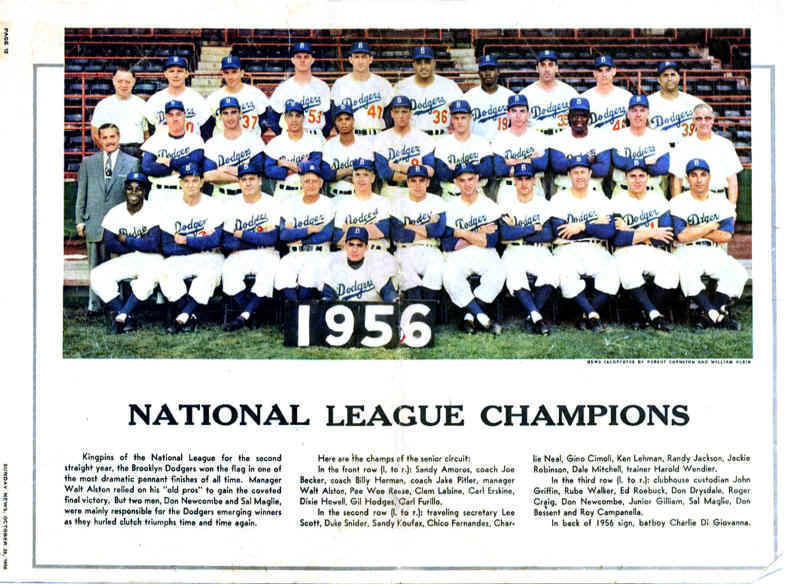

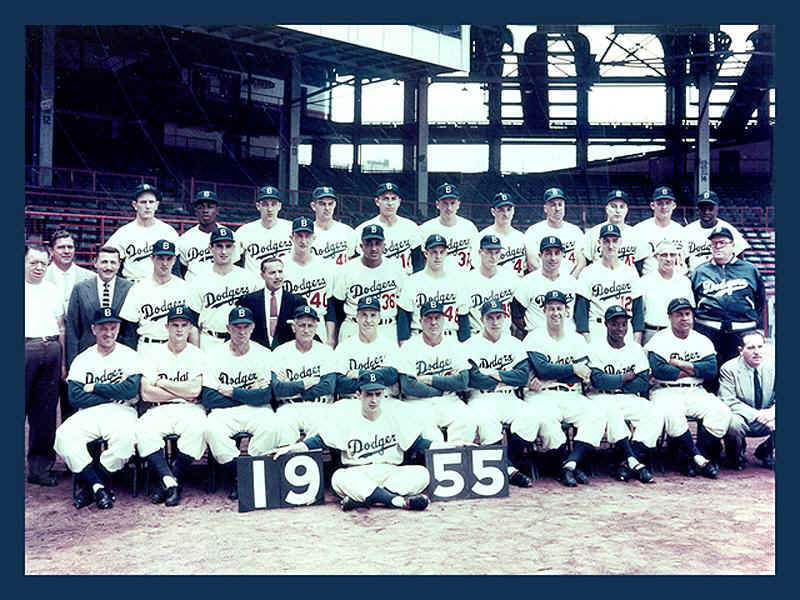

Other than winning the Pennant in 1916 and again in 1920, Athe team had limited success in the Nineteen-Teens, ‘Twenties and ‘Thirties, until the gifted Branch Rickey became managing owner. “Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman,” made the Dodgers perennial contenders. They hosted the 1949 All Star Game, and won National League Pennants in 1941, 1947, 1949, 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1956, but were defeated in the World Series six of these seven times by the New York Yankees. And so it was Brooklyn that gave birth to the immortal baseball slogan, “Wait Till Next Year!

1941

1947

1949

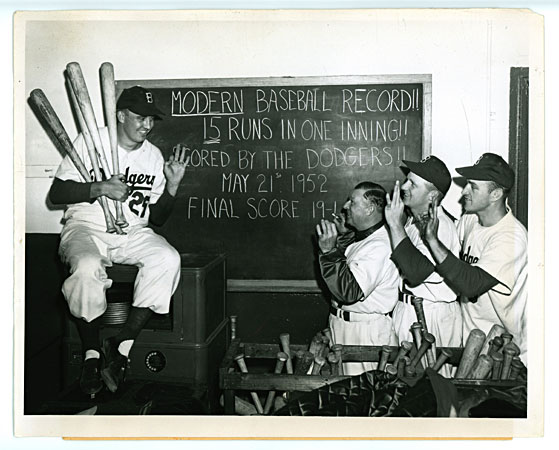

1952

1953

1956

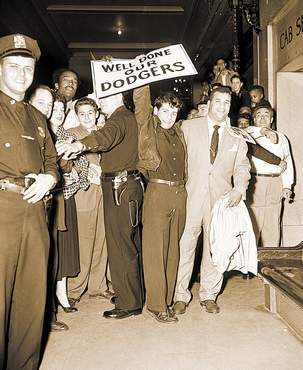

The only Brooklyn Dodgers team to ever win the World Series did so in 1955.

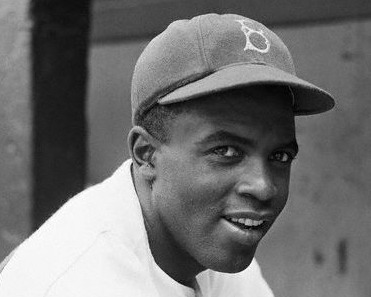

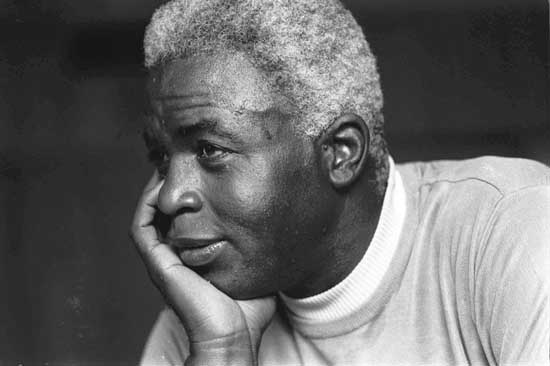

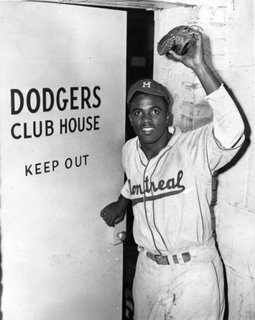

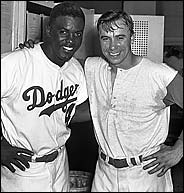

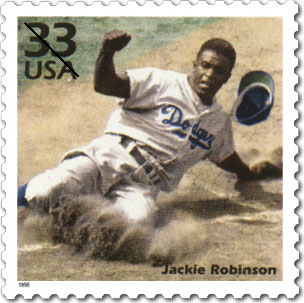

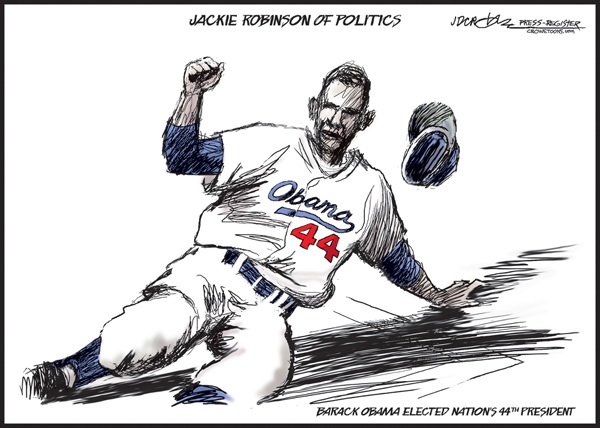

The ballpark has been featured in many books and films, both fiction and non-fiction. But the most historically significant aspect of Brooklyn Dodgers history was their breaking of the color barrier by signing a young, talented African-American player, Jackie Robinson, who first stepped onto the grass at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947. Winner of the first ever Rookie of the Year award and a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame, Robinson’s placement in the daily lineup ended almost 80 years of racial segregation in baseball. On the 50th anniversary of his debut in 1997, all of Major League Baseball retired Robinson’s jersey number, 42.

After the 1957 season, the Brooklyn Dodgers were unilaterally moved to Los Angeles by their unscrupulous owner, Walter O’Malley, in despite of almost eighty years of intimate association with the City of Brooklyn—ending an era.

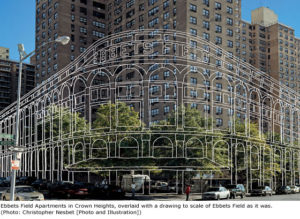

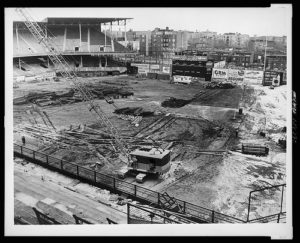

Ebbets Field, unused, was demolished on February 23, 1960.

April 15, 1947: The Day That Changed America Forever

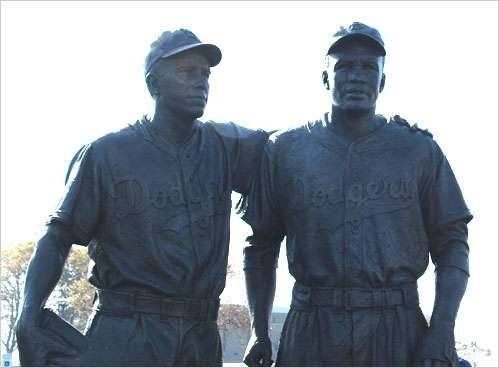

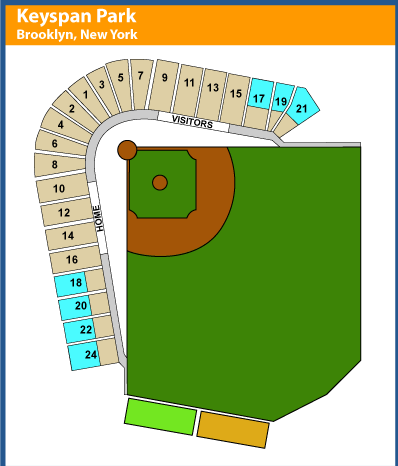

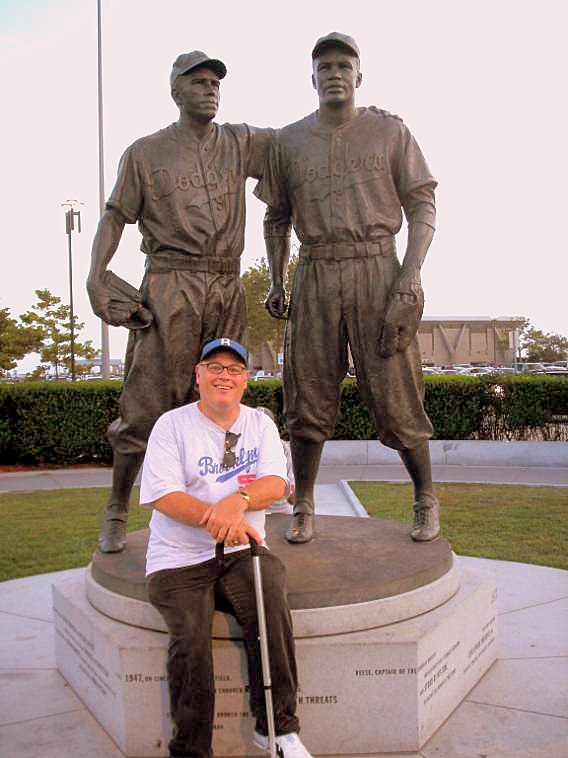

Pee Wee, Jackie and Me—KeySpan Park, July 13, 2008;

Jackie, Pee Wee, Spider Jorgensen and Eddie Stanky just moments before Jackie took the field—Ebbets Field, April 15, 1947

Pee Wee, Jackie and Me—KeySpan Park, July 13, 2008;

Jackie, Pee Wee, Spider Jorgensen and Eddie Stanky just moments before Jackie took the field—Ebbets Field, April 15, 1947

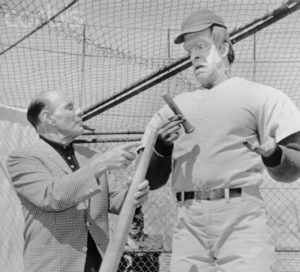

Jackie signs with the Dodgers while Branch Rickey looks on

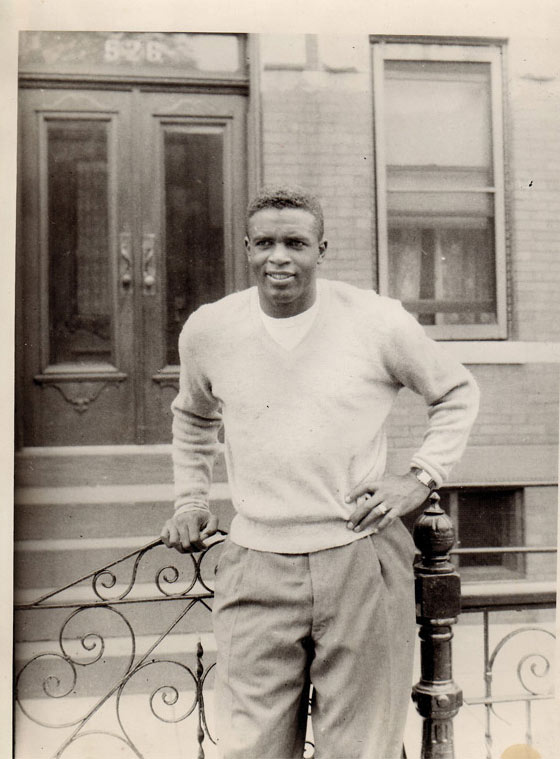

Jackie signs with the Dodgers while Branch Rickey looks on April 15, 1947 marked the beginnings of a seismic shift in America’s social structure, for that was the day that Jack Roosevelt “Jackie” Robinson (1919-1972) first stepped upon the green, green grass of the ballpark that was to be his home for the next nine years, Ebbets Field. By taking that momentous step, Jackie shattered the color line in our National Pastime, forcing too many unwilling Americans to acknowledge his presence and talents on the field. Although welcomed in ethnically and racially diverse Brooklyn, Jackie faced horrific resistance—even death threats— from fans and players in other cities. But by being the first Rookie of the Year, and MVP, and the man who still holds the Dodger record for the most steals of Home (19), Jackie changed America profoundly He may not have succeeded so well had it not been for Harold Henry “Pee Wee” Reese, a native Kentuckian, a son of the South, and the Dodgers’ team Captain. One day during a 1947 road trip, Pee Wee braved trash, spit, catcalls and threats to stride onto the field and embrace Jackie, telling all of America that he was a Brooklyn Dodger and was here to stay. The moment was immortalized in bronze at the entrance to KeySpan Park in Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, the home of the New York Mets “A” affiliate, the Brooklyn Cyclones. Pee Wee, Jackie and I shared a victorious moment together on July 13, 2008, after a Cyclones victory over the State College Spikes.

April 15, 1947 marked the beginnings of a seismic shift in America’s social structure, for that was the day that Jack Roosevelt “Jackie” Robinson (1919-1972) first stepped upon the green, green grass of the ballpark that was to be his home for the next nine years, Ebbets Field. By taking that momentous step, Jackie shattered the color line in our National Pastime, forcing too many unwilling Americans to acknowledge his presence and talents on the field. Although welcomed in ethnically and racially diverse Brooklyn, Jackie faced horrific resistance—even death threats— from fans and players in other cities. But by being the first Rookie of the Year, and MVP, and the man who still holds the Dodger record for the most steals of Home (19), Jackie changed America profoundly He may not have succeeded so well had it not been for Harold Henry “Pee Wee” Reese, a native Kentuckian, a son of the South, and the Dodgers’ team Captain. One day during a 1947 road trip, Pee Wee braved trash, spit, catcalls and threats to stride onto the field and embrace Jackie, telling all of America that he was a Brooklyn Dodger and was here to stay. The moment was immortalized in bronze at the entrance to KeySpan Park in Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, the home of the New York Mets “A” affiliate, the Brooklyn Cyclones. Pee Wee, Jackie and I shared a victorious moment together on July 13, 2008, after a Cyclones victory over the State College Spikes. I’ve included pictures of these three fine vessels as a matter of civic pride.

Why Brooklyn?

Brooklyn occupies 100 square miles of the extreme southwestern end of Long Island. Few Brooklynites even realize they are Long Islanders. When New Yorkers say “The Island” they usually mean the suburban counties of Nassau and Queens, which are not Boroughs of New York City. Likewise, “The City” is used to refer to Manhattan (and Manhattan alone).

Brooklyn was accessible to Manhattan only by ferry until 1883, when Washington Roebling completed the mighty Brooklyn Bridge, which spans the East River. At the time of its opening, the Brooklyn Bridge was the largest suspension bridge in the world. It is instantly recognizable by its granite towers, with their distinctive twin Gothic arches.

Brooklyn was its own city before Greater New York swallowed it whole in 1898 (by only a few hundred “yea” votes out of 70,000 cast). It was known as “The City Across The River” or “The City of Churches.” For much of its history, Brooklyn was an absolutely bucolic place to live, dotted with brownstone houses and farmsteads, the preserve of the descendants of the Dutch Burghers of New Amsterdam and their British successors. Brooklyn , in fact, in place names and historic associations, retains more of its Dutch flavor than any other Borough, right down to its name, an Anglicization of “Breukelen,” a town in The Netherlands.

As a Borough, it was big and klutzy, the unshaven bigger, younger blue-collar brother of chi-chi Beau Brummell Manhattan. Brooklyn’s population has always exceeded that of any other Borough, and in its own way, Brooklyn has been far more diverse and interesting than its more famous rival. Brooklyn neighborhoods were (and are) very unique in that they were (and are) small, densely populated, and largely ethnically homogeneous in and of themselves, being cheek-by-jowl with other such neighborhoods (sometimes groups shared neighborhoods, with varying levels of ease). Hence, there was largely Jewish Brownsville; there was (and is) largely Italian Bay Ridge; there was (and is) a Norwegian enclave in Bay Ridge, too; there was (and is) Hasidic Crown Heights and Hasidic Borough Park, and (was and is) an African-American section of Crown Heights.

Brooklyn’s wharves were busier than New York’s. It had more breweries than either Milwaukee or St. Louis. It’s said that over 400 languages are daily spoken in Brooklyn, more than any other place in the entire world, and that people from every nation can be found within its borders. Demographers tell us that 25% of all United States citizens can trace a connection back to Brooklyn. The closely-voted decision to join New York City is often referred to locally as “The Mistake of ’98” with good reason.

In the early twentieth century, Brooklyn grew at a fantastic rate as immigrants and the children of immigrants streamed (as they still do) into its hundred square miles seeking relief from the overcrowding of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The immigrants developed their own patois that reflected a mixture of their varying accents newly-leavened with the day-to-day details of Brooklyn life. For example:

“Oil” is a British lord. “Earl” is what you put in your car.

“Toity-Toid An Toid” is an intersection in Manhattan.

“Hey! Howya doin’?” is the proper form of address to any truck driver, your brother’s friend Kenny The Cop, the milkman, the mechanic, the plumber, the doctor, the lawyer, the local wiseguy, the President of the United States, and any English “Oil” who might be lost and asking directions. If he’s asking, you don’t tell him, you take him, and then you both get lost because once you’re out of your own neighborhood you might as well be in Timbuktu.

By the way, you might know one Doctor and one Lawyer, but you do know fifteen truck drivers, fourteen mechanics, eleven plumbers, seven retired milkmen, a hairdresser named Connie who’s married to Carmine (or else Rosalinda, and she calls her boyfriend Papi), a hundred wiseguys all named Paulie, and you once bought the President a slice and a soda, or at least the guy looked like him.

Nobody can sell you nothin’ or tell you nothin’, and they shouldn’t even try.

If you found a bag full of money on the street you’d ask around all day ’til you found the guy it belonged to so you could return it. Still full. (Since you know a hundred wiseguys you also know that this is not just an act of kindness, it’s a probable act of self-preservation.)

A “stoop” is where you’d sit when you were “downstairs”. “Tar Beach” up on the roof is where you’d spend your summers. “The Country” is where you’d go in the summer if you were lucky.

An egg cream was (and is) a tasty drinkable concoction containing neither eggs nor cream, but containing a species of carbonated water (which no one in their right mind ever called Club Soda) that was brought to you weekly courtesy of The Seltzer Man. The Seltzer Man “worked like a horse” hefting cases of the stuff onto his shoulder in heavy blue or green or clear siphon bottles and climbing however many flights of stairs there were in order to service his customers. And why? So his kid could go to College, maybe be a doctor or a lawyer. To make an egg cream, Seltzer was mixed with Fox’s U-bet chocolate syrup and milk (with unhomogenized cream on top) from Sheffield Dairy or Borden’s (Borden’s was the preferred product in my house growing up, since it had a smiling Elsie the Cow on the bottle). Thus was this quintessentially Brooklyn vin ordinaire brought into existence.

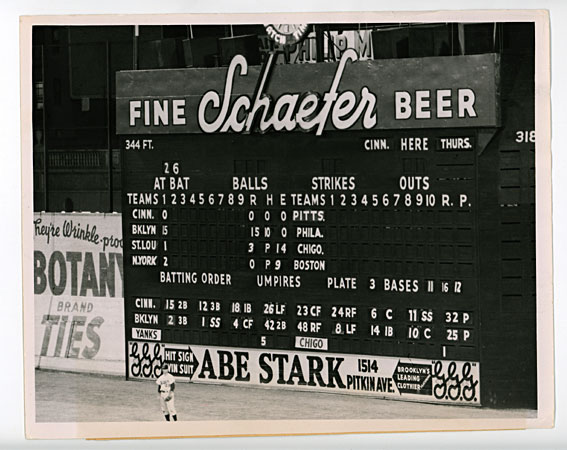

Schaefer and Rheingold were the beers of choice, both brewed locally. Budweiser was some unheard-of brand that that guy, he never talks to nobody, bought at that place nobody shops at, y’know the one I mean, right?

Wetson’s was much better than McDonald’s, if you could even find a McDonald’s—why bother? We had Wetson’s. Chicken Delight, yes. Kentucky Fried Chicken, uh, where’s Kentucky, ma?

Pickles could be bought on the street straight out of an open pickle barrel, and nobody spit or threw their cigarette butts into these community treasures. The penalty for doing so was unthinkable. The subway was a nickel, then it was a dime. A comfortable apartment was $60 a month. Bargains galore were available from the pushcarts on Blake Avenue. As late as 1963, a horse-drawn vegetable wagon would clop down my street selling its wares. Nearby Hegeman Avenue had an unpaved lane—a dirt road—in East New York.

Ruby the Knish Man called his wares from a pushcart there (and everywhere else in Brooklyn, and in The Country). After I grew up and learned about cloning it solved the mystery of how Ruby managed to be in Canarsie, on Livonia Avenue, and upstate at Moonlight Cottages all at the same time.

And then there was baseball . . .

In the midst of this mosaic, there were (and are) central gathering places for the “tribes” of Brooklyn. Brooklyn had (and has) Prospect Park, far better than Central Park, even in the minds of their joint creators. Coney Island means the Cyclone Roller Coaster, Nathan’s, and the more recent Brooklyn Cyclones baseball team. Longer ago, there was Ebbets Field and the Dodgers.

Baseball might not have been invented in Brooklyn, but Brooklyn, city and borough, has contributed greatly to our National Pastime. The curve ball was invented in Brooklyn, as was the idea of actually selling tickets to spectators. The warning track was a Brooklyn innovation, meant to keep “Pistol Pete” Reiser from slamming at full speed into the unpadded outfield wall. He did anyway, and shortened his career. Brooklyn padded its walls. Concerned about beanballs, Brooklyn introduced the batting helmet. And it was Brooklyn that played host in the first-ever televised game. Brooklyn, with its diversity, its innate tolerance, and its flair for invention, was the natural team to draft Jackie Robinson.

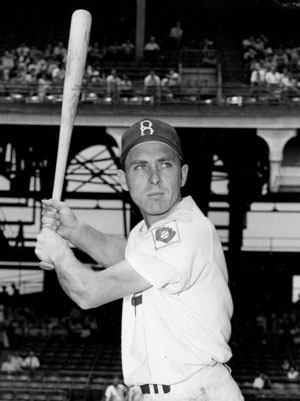

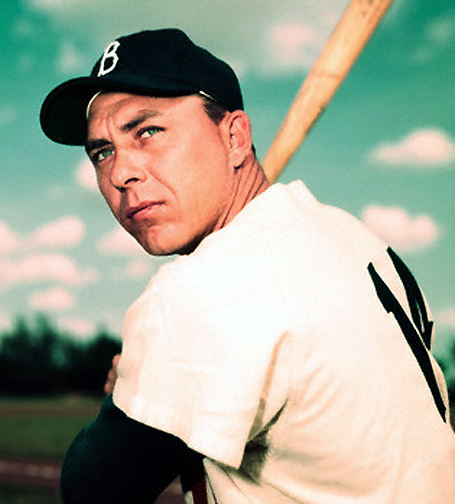

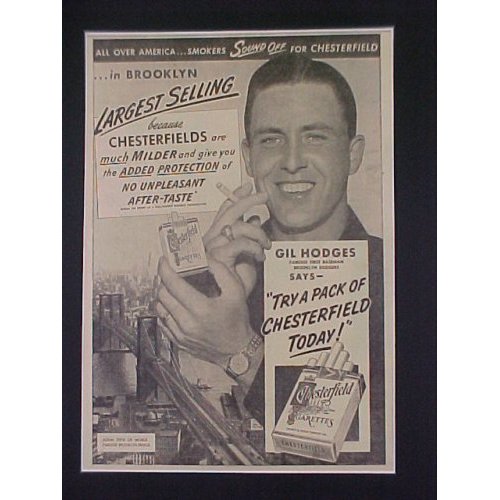

The Dodgers (a. k. a. “Dem Bums”) were always in contention but never managed to get past the Yankees, except once, in 1955. It was, in all respects, a local team. Gil Hodges, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, and even Jackie Robinson lived down the block. But things were changing. In ’57 they were gone, courtesy of Walter O’Malley. A Brooklyn joke told to this day still drips with bitterness: “If Hitler, Stalin, and O’Malley were walking toward you and you only had two bullets in your gun, who would you shoot? O’Malley–twice.”

Growing up, I knew there had been three baseball teams—The Yankees far away up in The Bronx, those forgotten guys from the Polo Grounds (i.e., the Giants or “Jints” in our lexicon), and the Dodgers, who were now known as the Los Angeles Traitors. For years, I thought that was the new name of the team.

What I never knew was how much my family had loved the Dodgers. They were never spoken of, except briefly and with a certain wistfulness. I was much older when my father talked about seeing his first baseball game at Ebbets Field. It was Jackie Robinson’s and Duke Snider’s first game there, too. As an adult, I asked my Dad why he had never kept his annual promise to take me to Yankee Stadium (over time, it became the only promise he never kept to me). He looked far away and said, “After the Dodgers. After Ebbets Field. What was the point?”

My Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Fame

Given the vast number of characters—and for many of them, the term “characters” is an exact description—that have passed through the blue gates of Brooklyn Dodgers history, this personal Hall of Fame cannot even begin to be complete. Some of these people were world-beaters and some of them couldn’t get out of their own way. Some were exceptionally talented. Many of them were ordinary men and women who found themselves in a place—Ebbets Field—at a time not very long ago at all, when all things seemed possible. It was a colorful world bequeathed to us in black and white, a world many of us remember, even if, like me, we were born even as it vanished.

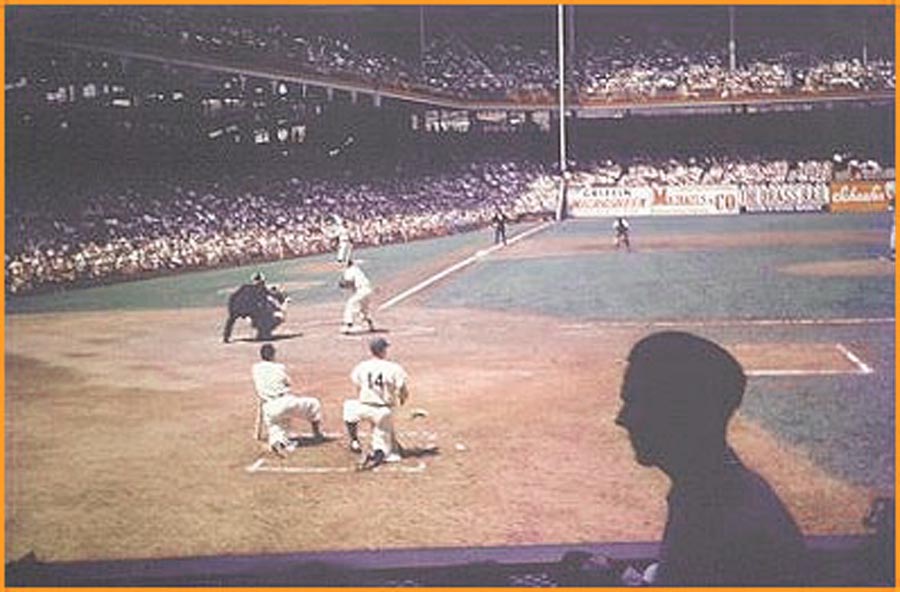

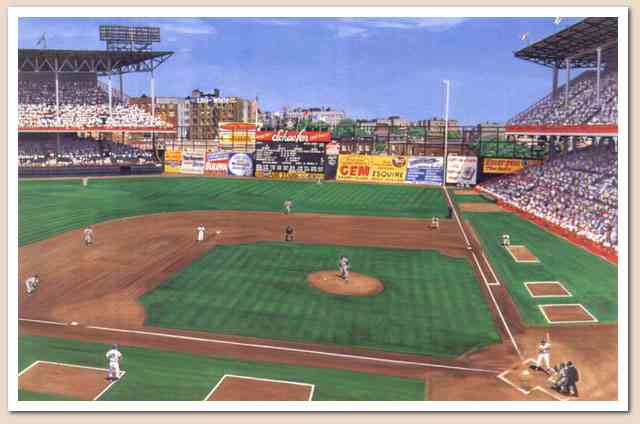

EBBETS FIELD: This jewelry-box ballfield on Flatbush Avenue was the stage on which so much of Brooklyn Dodgers history was played out, an intimate, almost wedge-shaped ballpark where a fan in the field level seats could tap a player in the On Deck Circle on the shoulder and ask him to autograph his scorecard. Seating about 32,000, Ebbets Field opened in 1913 and closed forever in 1960 as a wrecker’s ball—painted obscenely to look like a baseball—began smashing it to bits. Since its destruction, the ballpark has passed into legend. The current crop of newly-built ballparks all try to copy Ebbets Field, but they are all sad counterfeits that lack the magic of this original Field of Dreams.

EBBETS FIELD: This jewelry-box ballfield on Flatbush Avenue was the stage on which so much of Brooklyn Dodgers history was played out, an intimate, almost wedge-shaped ballpark where a fan in the field level seats could tap a player in the On Deck Circle on the shoulder and ask him to autograph his scorecard. Seating about 32,000, Ebbets Field opened in 1913 and closed forever in 1960 as a wrecker’s ball—painted obscenely to look like a baseball—began smashing it to bits. Since its destruction, the ballpark has passed into legend. The current crop of newly-built ballparks all try to copy Ebbets Field, but they are all sad counterfeits that lack the magic of this original Field of Dreams.

CHARLES EBBETS (1859-1925): Starting out as a ticket-taker, he eventually bought the team and built the ballpark that bore his name. When he bought the Dodgers he was offered a number of very lucrative deals to move the team to another city, but he refused, believing that the Dodgers were the common property of all Brooklynites and that he was merely the custodian of their trust. He was (in part) responsible for starting the famous feud and rivalry between the Dodgers and the New York Giants, when, after a personal disagreement with Giants owner John McGraw, Ebbets swore he “wouldn’t give McGraw the smoke off his tea.” McGraw felt likewise, and their mutual dislike colored both teams, a bitter rivalry that even transcended both teams’ removal to California. When Charley died, his heirs and the heirs of his partners fell into a disagreement over ownership and management of the team that lasted until they all sold out. Sadly, they ended up selling out to a group which included Walter O’Malley, who didn’t share Charley’s sense of loyalty to Brooklyn or to Dodger fans.

CHARLES EBBETS (1859-1925): Starting out as a ticket-taker, he eventually bought the team and built the ballpark that bore his name. When he bought the Dodgers he was offered a number of very lucrative deals to move the team to another city, but he refused, believing that the Dodgers were the common property of all Brooklynites and that he was merely the custodian of their trust. He was (in part) responsible for starting the famous feud and rivalry between the Dodgers and the New York Giants, when, after a personal disagreement with Giants owner John McGraw, Ebbets swore he “wouldn’t give McGraw the smoke off his tea.” McGraw felt likewise, and their mutual dislike colored both teams, a bitter rivalry that even transcended both teams’ removal to California. When Charley died, his heirs and the heirs of his partners fell into a disagreement over ownership and management of the team that lasted until they all sold out. Sadly, they ended up selling out to a group which included Walter O’Malley, who didn’t share Charley’s sense of loyalty to Brooklyn or to Dodger fans.

ZACK WHEAT (1888-1972): The Dodgers’ greatest hitter with 2,884 to his credit, Wheat began playing during the Dead Ball Era. Amazingly, he hit over .300 for 14 of his 19 seasons and finished his career with a .317 average. Just after Charles Ebbets’ death he was named to manage the Dodgers, but when owner Ed McKeever died less than two weeks later, Wilbert “Uncle Robbie” Robinson replaced him.

ZACK WHEAT (1888-1972): The Dodgers’ greatest hitter with 2,884 to his credit, Wheat began playing during the Dead Ball Era. Amazingly, he hit over .300 for 14 of his 19 seasons and finished his career with a .317 average. Just after Charles Ebbets’ death he was named to manage the Dodgers, but when owner Ed McKeever died less than two weeks later, Wilbert “Uncle Robbie” Robinson replaced him.

THE BROOKLYN DODGER SYM-PHONY: To call the Sym-Phony a group of dedicated amateur musicians would be to grant them a degree of musical competence many magnitudes above what actually existed. “They couldn’t hit a note,” said Don Newcombe. Maybe not, but these guys had a great deal of fun parading through the stands with their brass instruments and big bass drum, adding musical punctuation to every step (and misstep) on the field. “Three Blind Mice” was the theme song for the umpires, “The Worms Crawl In, The Worms Crawl Out” greeted struck out players as they returned to the dugout, and no matter how savvy the player, a big “ba-boom” greeted every player as his rump hit the bench. A totally spontaneous outgrowth of the madcap energy that effused Ebbets Field, the Sym-Phony drew the ire of the powerful Musicians’ Union , who accused owner Walter O’Malley of allowing non-union performers to entertain at Ebbets Field. To prove the point that anyone could play an instrument without being an “entertainer,” O’Malley , in a rare moment of business whimsy, announced “Music Depreciation Night,” and allowed any fan carrying an instrument to enter the park for free. Kazoos, whistles, ocarinas, jews’-harps, accordians, trumpets, drums, violins, upright basses, tubas and sousaphones, a woodwind section, and even two pianos set up a still-remembered caterwauling that night “to beat the band” or, more accurately, the Musicians’ Union. The union dropped the matter. The band played on.

THE BROOKLYN DODGER SYM-PHONY: To call the Sym-Phony a group of dedicated amateur musicians would be to grant them a degree of musical competence many magnitudes above what actually existed. “They couldn’t hit a note,” said Don Newcombe. Maybe not, but these guys had a great deal of fun parading through the stands with their brass instruments and big bass drum, adding musical punctuation to every step (and misstep) on the field. “Three Blind Mice” was the theme song for the umpires, “The Worms Crawl In, The Worms Crawl Out” greeted struck out players as they returned to the dugout, and no matter how savvy the player, a big “ba-boom” greeted every player as his rump hit the bench. A totally spontaneous outgrowth of the madcap energy that effused Ebbets Field, the Sym-Phony drew the ire of the powerful Musicians’ Union , who accused owner Walter O’Malley of allowing non-union performers to entertain at Ebbets Field. To prove the point that anyone could play an instrument without being an “entertainer,” O’Malley , in a rare moment of business whimsy, announced “Music Depreciation Night,” and allowed any fan carrying an instrument to enter the park for free. Kazoos, whistles, ocarinas, jews’-harps, accordians, trumpets, drums, violins, upright basses, tubas and sousaphones, a woodwind section, and even two pianos set up a still-remembered caterwauling that night “to beat the band” or, more accurately, the Musicians’ Union. The union dropped the matter. The band played on.

DAZZY VANCE (1891-1961): Vance was the brightest star in the Dodgers universe during the height of The Daffiness Boys Era, when Brooklyncouldn’t seem to do anything right. Following their loss to the Cleveland Indians in the 1920 World Series, the Dodgers suffered a twenty year collapse. Although individual players like Vance played phenomenal ball, the team as a whole was so bad that it was said (after a brief winning streak) that “overconfidence could cost the Dodgers seventh place,” and indeed, they hardly ever rose above sixth, a confirmed second division ballclub. Like Tom Seaver and the Mets 40 years later,Vance became ‘the franchise’. In his rookie year of 1922, he posted 18 wins and 12 losses with a 3.70 Earned Runs Average and a league-leading 134 strikeouts. His best season was 1924. He led the NL in wins (28), strikeouts (262) and ERA (2.16) and won the Triple Crown. He was named league MVP. Vance pitched a no-hitter in 1925. Vance led the National League in strikeouts for seven consecutive years (1922 – 1928), and retired with a 197-140 record, posting 2045 strikeouts and a 3.24 ERA overall.

DAZZY VANCE (1891-1961): Vance was the brightest star in the Dodgers universe during the height of The Daffiness Boys Era, when Brooklyncouldn’t seem to do anything right. Following their loss to the Cleveland Indians in the 1920 World Series, the Dodgers suffered a twenty year collapse. Although individual players like Vance played phenomenal ball, the team as a whole was so bad that it was said (after a brief winning streak) that “overconfidence could cost the Dodgers seventh place,” and indeed, they hardly ever rose above sixth, a confirmed second division ballclub. Like Tom Seaver and the Mets 40 years later,Vance became ‘the franchise’. In his rookie year of 1922, he posted 18 wins and 12 losses with a 3.70 Earned Runs Average and a league-leading 134 strikeouts. His best season was 1924. He led the NL in wins (28), strikeouts (262) and ERA (2.16) and won the Triple Crown. He was named league MVP. Vance pitched a no-hitter in 1925. Vance led the National League in strikeouts for seven consecutive years (1922 – 1928), and retired with a 197-140 record, posting 2045 strikeouts and a 3.24 ERA overall.

“WEE” WILLIE “HIT ‘EM WHERE THEY AIN’T” KEELER (1872-1923): Standing approximately 5’7″ (some sources say he was as short as 5’4″) and weighing 140 pounds, the Brooklyn-born Keeler was one of the smallest players ever to play professional baseball. He was also an impressive long ball and power hitter during the Dead Ball Era. His .385 career batting average is the highest batting average in history for a player with 1000 + (in Keeler’s case, 1147) hits . He hit over .300 16 times in 19 seasons, and hit over .400 once.

“WEE” WILLIE “HIT ‘EM WHERE THEY AIN’T” KEELER (1872-1923): Standing approximately 5’7″ (some sources say he was as short as 5’4″) and weighing 140 pounds, the Brooklyn-born Keeler was one of the smallest players ever to play professional baseball. He was also an impressive long ball and power hitter during the Dead Ball Era. His .385 career batting average is the highest batting average in history for a player with 1000 + (in Keeler’s case, 1147) hits . He hit over .300 16 times in 19 seasons, and hit over .400 once.

GOODDING (d. 1963): Was an Ebbets Field institution. Hired as an organist in 1942 to provide musical accompaniment at the games and to sing the National Anthem, Goodding’s voice was classically-trained. Her renditions of The Star Spangled Banner had a timeless quality. Even someone who has never heard of Goodding will instantly recognize the style. Goodding wrote the team’s theme song, Follow The Dodgers, which she played every time the team took the field.

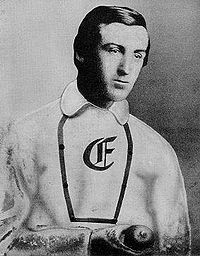

JIM CREIGHTON (1841-1862): After 1859, he played for the Brooklyn Excelsiors, one of the several teams that later converged to form the Dodgers in the 1880s. Creighton was baseball’s first superstar, credited with inventing the fastball. At age 21, Creighton died of an unknown abdominal complaint.

JIM CREIGHTON (1841-1862): After 1859, he played for the Brooklyn Excelsiors, one of the several teams that later converged to form the Dodgers in the 1880s. Creighton was baseball’s first superstar, credited with inventing the fastball. At age 21, Creighton died of an unknown abdominal complaint.

FLOYD CAVES “THE OTHER BABE” HERMAN (1903-1987): Babe Herman personified the spirit of The Daffiness Boys of the 1920s. Although Babe was a superb hitter, posting a .393 average, Herman was no competition for the Babe from the Bronx. His fielding was careless, and he led the league in errors in 1927. “He wore a glove because it was the custom,” Fresco Thompson said. Babe Herman scoffed at his own talent by saying, “If you see a guy and you think its me, throw some fly balls at him. If he catches them—It ain’t me.” At least twice he stopped on the basepaths to watch homers fly over the fence, costing the Dodgers an extra run. Herman claimed to have been bonked on the head by several fly balls (though he later admitted to exaggerating for effect). Once, while being interviewed he shocked the reporter by putting a lit cigar into his pants pocket without first extinguishing it. One gaffe that did become legendary resulted from his doubling into a double play. For some reason, he ended up at third with Dazzy Vance and Chick Fewster. All three men were tagged out. Sour Dodger fans never forgot the incident: “The Dodgers have three men on base! Yeah? Which base?”

BABE RUTH (1895-1948): Babe Ruth? Babe Ruth was a Brooklyn Dodger? Yes folks, he sure was. Hired in 1938 by Larry MacPhail, Babe Ruth was a Dodger First Base coach, not a player. Although he had been tapped as a potential manager, even the legendarily alcoholic MacPhail grimaced at The Babe’s drinking habits, but even more so at his lack of dependability. The Babe came and went as he pleased, and sometimes never showed up for work at all. Ruth lasted only a single season in True Dodger Blue. But The Babe was a draw. Fans came to EbbetsField early for batting practice, hoping to see the Sultan of Swat do his thing. And he did. None of his Ebbets Field homers counted toward his record, but I’ve heard from those who were there that the rockets he sent over the wall toward Bedford Avenue always brought the fans to their feet cheering, and, even sometimes, gaping openmouthed.

Which brings us to . . .

LELAND STANFORD “LARRY” MACPHAIL (1890-1975): The Dodgers might never have become the Dodgers without Larry MacPhail. Impresario, executive, innovator, mean drunk, and madman, MacPhail brought baseball into the modern age by introducing night games to the sport, eschewing trains and using airplanes for team travel, breaking the “Gentleman’s Agreement” among the New York team owners not to radio broadcast games, had Dodger games broadcast on New York’s early experimental TV station W2XBS, spending money to upgrade Ebbets Field, spending money to buy top players. It’s said that Dodgers part-owner Steve McKeever died of a stroke after finding out that Larry paid Fifty Thousand Dollars for Dolph Camilli.

Some of Larry’s innovations went nowhere. Fans and players alike disliked the yellow baseballs he experimented with, and his glitzy satin night game uniforms looked good under the new lights at Ebbets Field, but were a bit too fey; today, they’re valuable collector’s items.

But some of his innovations were the stuff that remade the team. Bringing Red Barber to New York to be the on-air broadcaster changed the relationship of the fans and the team in a profound way, forming a bond that endures (in memory) to this day; spending money meant that more fans came to a more comfortable Ebbets Field to watch a team in serious contention. Larry was actually forced on the Dodgers’ recalcitrant owners by the Brooklyn Trust Company, to whom the team was over $1,000,000.00 in debt. In 1937, Ebbets Field, was crumbling due to neglect, and the local utility companies were threatening to turn off the water, lights and telephones in the stadium. The creditors demanded that the ownership resolve their decades-long internal squabbles, and that a new management team be appointed, subject to bank approval. The chastened owners appointed Larry. The Dodgers won their first Pennant in a generation, in 1941, but lost that year’s World Series to the Yankees in the first Subway Series.

MacPhail’s impact can be summed up simply by saying that in the 38 years before MacPhail, the Dodgers had won three pennants; in the 20 years following his arrival they won seven and lost in playoffs two times after finishing tied for first.

MacPhail was rancorous, particularly when he was drunk, which was often. According to Leo Durocher, “There is a thin line between genius and insanity, and in Larry’s case it was sometimes so thin you could see him drifting back and forth.” Leo would know. In his years as Field Manager under Larry, MacPhail fired Durocher at least 60 times. The blacked-out Larry frequently didn’t remember firing Durocher in the glare of a brain-frying “morning after,” and would fire him again for not showing up at the stadium on schedule.

Larry was seized with patriotic fervor after Pearl Harbor, and so he enlisted, selling his interest to Branch Rickey. He bought an interest in the Yankees after the war, but was bought out quickly. His histrionic behavior was less tolerable to the proper Bronx Bombersthan to the freewheeling Brooklyn Bums.

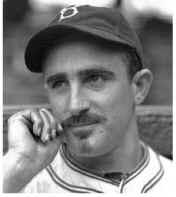

STANLEY GEORGE “FRENCHY” BORDAGARAY (1910-2001): Deserving of an Honorable Mention, Frenchy was a utility player who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1936-37, and then again in the lean war years of 1942-1945. While Frenchy’s on-the-field abilities were colorless (he batted .283 and had 13 home runs over an eleven year career), he was famous as the only Major League player to sport a moustache between the late Nineteenth Century and the late Twentieth Century. He was also quite possibly the only ballplayer ever suspended for spitting on the field. When asked about his suspension, a bemused Frenchy said, “It was more than I expectorated.”

STANLEY GEORGE “FRENCHY” BORDAGARAY (1910-2001): Deserving of an Honorable Mention, Frenchy was a utility player who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1936-37, and then again in the lean war years of 1942-1945. While Frenchy’s on-the-field abilities were colorless (he batted .283 and had 13 home runs over an eleven year career), he was famous as the only Major League player to sport a moustache between the late Nineteenth Century and the late Twentieth Century. He was also quite possibly the only ballplayer ever suspended for spitting on the field. When asked about his suspension, a bemused Frenchy said, “It was more than I expectorated.”

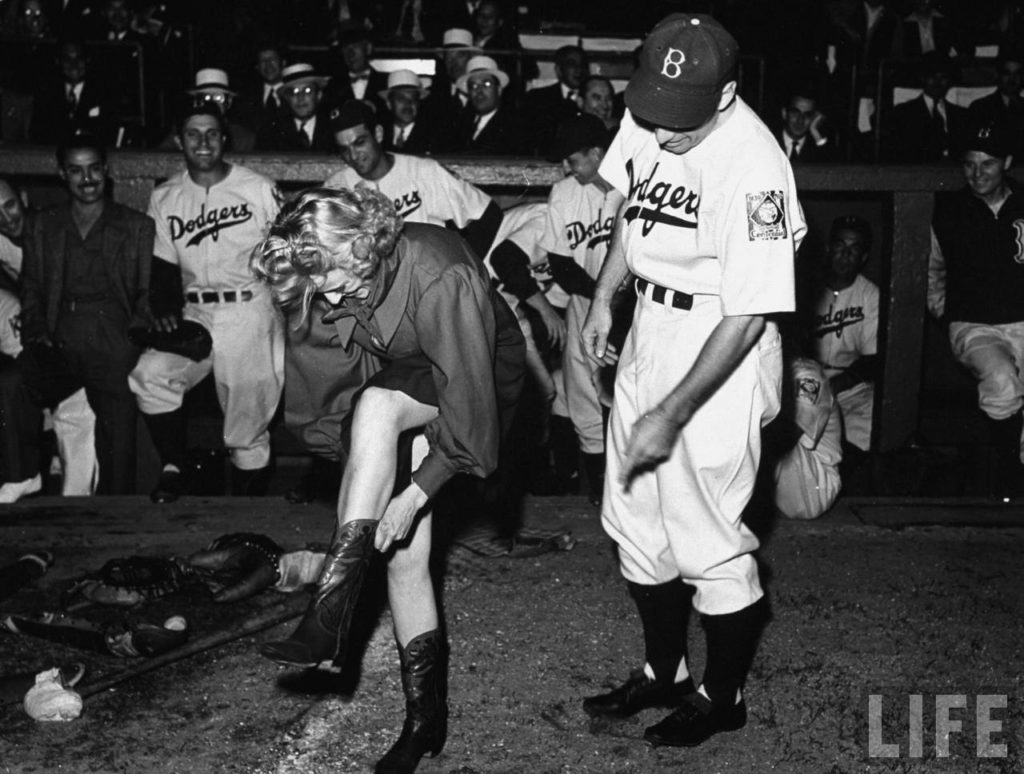

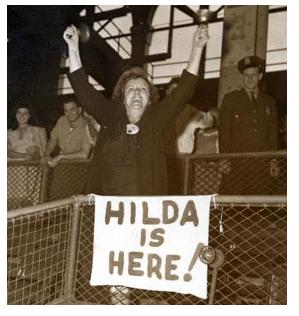

HILDA CHESTER (1897-1987): The most famous Dodger fan of all time was Hilda Chester, a large, loud, gravel-voiced, muu-muu clad woman with a mop of stringy hair. She first appeared at Ebbets Field in the 1920s, and by the 1930s she was one of hundreds of Ebbets Field regulars.

HILDA CHESTER (1897-1987): The most famous Dodger fan of all time was Hilda Chester, a large, loud, gravel-voiced, muu-muu clad woman with a mop of stringy hair. She first appeared at Ebbets Field in the 1920s, and by the 1930s she was one of hundreds of Ebbets Field regulars.

After suffering a heart attack in the early 1940s, her doctor dissuaded her from yelling at the games, so when she returned to Ebbets Field, she brought a frying pan and an iron ladle, making so much noise with them that she became an Ebbets Field attraction unto herself.

Well-known to all, she was even invited to travel with the team on short road trips. One day, after a particularly bad showing, she berated Duke Snider, who responded, “Hilda, why don’t you go home and shave?”

The Dodgers presented Hilda with the first of her famous cowbells in the 1930s. When she suffered a second heart attack in the mid-1940s, several of the players went to visit her in the hospital, including Leo Durocher, who became Hilda’s special hero. Her fondness for Durocher transcended even her fondness for the Dodgers, and after Durocher went to manage the Giants in 1948, she could be found at the Polo Grounds as well as at Ebbets Field.

BARNEY STEIN (1908-1993): Barney Stein was an indefatigable photographer, always seeking the perfect picture. He once climbed the Triborough Bridge while it was under construction to take panoramic shots from the top of one of the towers. He photographed the famous, the not-so-famous, and the infamous. His cry, “Uno mas! One more!” was a familiar sound around Ebbets Field. Barney became the official Dodgers team photographer in 1937 and remained with the team until its move from Brooklyn in 1957. Afterward, he made a photographic record of the 1960 demise of Ebbets Field. A fine collection of his work for the Dodgers can be found in Through A Blue Lens.

BARNEY STEIN (1908-1993): Barney Stein was an indefatigable photographer, always seeking the perfect picture. He once climbed the Triborough Bridge while it was under construction to take panoramic shots from the top of one of the towers. He photographed the famous, the not-so-famous, and the infamous. His cry, “Uno mas! One more!” was a familiar sound around Ebbets Field. Barney became the official Dodgers team photographer in 1937 and remained with the team until its move from Brooklyn in 1957. Afterward, he made a photographic record of the 1960 demise of Ebbets Field. A fine collection of his work for the Dodgers can be found in Through A Blue Lens.

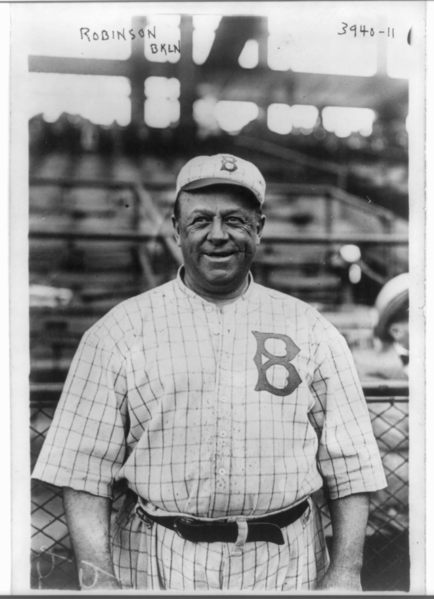

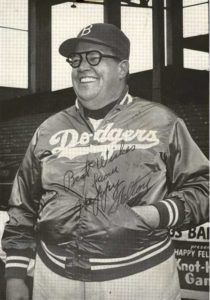

WILBERT ROBINSON (1863-1934): Eighteen seasons (1914-1931) as the Dodgers’ field manager earned Robinson the fond nickname of “Uncle Robbie” and the team he managed acquired the alternate name of “Robins” (his immediate successor was Max Canaris, and the sportswriters started calling the team the “Canaries,” but it didn’t catch on and neither did Canaris). Uncle Robbie has the distinction of winning more Dodger games ( 1,375 ) than any other manager in the team’s history. Not only was he the field manager, but he was also (briefly) the general manager and (even more briefly) the President of the Dodger organization, as a compromise candidate between the Ebbets heirs and the McKeever heirs. Uncle Robbie brought the team to two World Series, but he also oversaw the team’s near collapse in the 1920s. During the Daffy Dodger days Uncle Robbie barely managed to manage. Things became so dark that he created a “Boneheads Club,” a Dodger version of the stocks, to which any goofy player would be elected. Robbie immediately became the first member and President of the Boneheads, when he entrained the team and arrived for a scheduled road game a day early. Trying to set some kind of bizarre record, he attempted to catch a baseball dropped from an airplane, but was surprised by a practical joke when a grapefruit splattered over his head. Though he was generally unlucky with his team, he did groom an excellent pitching staff, including Dazzy Vance and Burleigh Grimes. Despite (or perhaps because of) the Daffiness Boys’ dismal record, the team became the beloved “Brooklyn Bums” on his watch. When Uncle Robbie died, he was profoundly mourned by all baseball-crazy Brooklynites.

WILBERT ROBINSON (1863-1934): Eighteen seasons (1914-1931) as the Dodgers’ field manager earned Robinson the fond nickname of “Uncle Robbie” and the team he managed acquired the alternate name of “Robins” (his immediate successor was Max Canaris, and the sportswriters started calling the team the “Canaries,” but it didn’t catch on and neither did Canaris). Uncle Robbie has the distinction of winning more Dodger games ( 1,375 ) than any other manager in the team’s history. Not only was he the field manager, but he was also (briefly) the general manager and (even more briefly) the President of the Dodger organization, as a compromise candidate between the Ebbets heirs and the McKeever heirs. Uncle Robbie brought the team to two World Series, but he also oversaw the team’s near collapse in the 1920s. During the Daffy Dodger days Uncle Robbie barely managed to manage. Things became so dark that he created a “Boneheads Club,” a Dodger version of the stocks, to which any goofy player would be elected. Robbie immediately became the first member and President of the Boneheads, when he entrained the team and arrived for a scheduled road game a day early. Trying to set some kind of bizarre record, he attempted to catch a baseball dropped from an airplane, but was surprised by a practical joke when a grapefruit splattered over his head. Though he was generally unlucky with his team, he did groom an excellent pitching staff, including Dazzy Vance and Burleigh Grimes. Despite (or perhaps because of) the Daffiness Boys’ dismal record, the team became the beloved “Brooklyn Bums” on his watch. When Uncle Robbie died, he was profoundly mourned by all baseball-crazy Brooklynites.

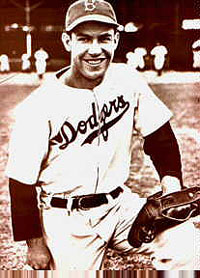

“PISTOL” PETE REISER (1919-1981): Widely considered one of the finest all-around baseball players ever, Reiser was an on-field sensation who played with an aggressive, almost suicidal, style. He fractured his skull running into the outfield wall on one occasion (but still made the throw back to the infield), was temporarily paralyzed on another and was taken off the field on a stretcher many times. On one occasion Pete was given his Last Rites in the ballpark. Leo Durocher, who was Pete’s first Major League manager, reflected many years later that in terms of talent, skill, and potential, there was only one other player comparable to Pete Reiser, and that was Willie Mays: “Willie Mays had everything. Pete Reiser had everything but luck.” Pete’s professional career lasted only twelve years, and was constantly interrupted by injuries. The Dodgers created the first purpose-built warning track to help Pete protect himself, but Pete disregarded it. Eventually, the Dodgers padded the walls, but Reiser’s career had gone into eclipse by then. Repeated closed head injuries affected his vision and his coordination, prematurely ending what might have been a stellar career.

“PISTOL” PETE REISER (1919-1981): Widely considered one of the finest all-around baseball players ever, Reiser was an on-field sensation who played with an aggressive, almost suicidal, style. He fractured his skull running into the outfield wall on one occasion (but still made the throw back to the infield), was temporarily paralyzed on another and was taken off the field on a stretcher many times. On one occasion Pete was given his Last Rites in the ballpark. Leo Durocher, who was Pete’s first Major League manager, reflected many years later that in terms of talent, skill, and potential, there was only one other player comparable to Pete Reiser, and that was Willie Mays: “Willie Mays had everything. Pete Reiser had everything but luck.” Pete’s professional career lasted only twelve years, and was constantly interrupted by injuries. The Dodgers created the first purpose-built warning track to help Pete protect himself, but Pete disregarded it. Eventually, the Dodgers padded the walls, but Reiser’s career had gone into eclipse by then. Repeated closed head injuries affected his vision and his coordination, prematurely ending what might have been a stellar career.

WESLEY BRANCH RICKEY (1881-1965): Branch Rickey was a teetotaling and religious Methodist who never came to games on Sundays. Sometimes hortatory and sometimes insufferably self-righteous, he was also a noted raconteur and a human being dedicated to fairness and justice. He took the helm from Larry MacPhail, and became a part owner of the team. As Brooklyn Dodger General Manager from 1941 to 1950, he came to know a wide variety of human beings, reprobates and reformers both. Branch Rickey invented the modern farm system in baseball. He founded Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida, as a dedicated training facility for both raw young talent and established players. It was said of Rickey that he had the singular ability of being able to assess the strengths and weaknesses of Minor Leaguers, talent and physique both, by observation, and to make amazingly accurate predictions as to the arc of a player’s career. He is, of course, best known as the man who signed Jackie Robinson and broke the color barrier in Major League baseball, but he was also responsible for signing all the stalwarts who became known collectively as “The Boys of Summer.”

WESLEY BRANCH RICKEY (1881-1965): Branch Rickey was a teetotaling and religious Methodist who never came to games on Sundays. Sometimes hortatory and sometimes insufferably self-righteous, he was also a noted raconteur and a human being dedicated to fairness and justice. He took the helm from Larry MacPhail, and became a part owner of the team. As Brooklyn Dodger General Manager from 1941 to 1950, he came to know a wide variety of human beings, reprobates and reformers both. Branch Rickey invented the modern farm system in baseball. He founded Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida, as a dedicated training facility for both raw young talent and established players. It was said of Rickey that he had the singular ability of being able to assess the strengths and weaknesses of Minor Leaguers, talent and physique both, by observation, and to make amazingly accurate predictions as to the arc of a player’s career. He is, of course, best known as the man who signed Jackie Robinson and broke the color barrier in Major League baseball, but he was also responsible for signing all the stalwarts who became known collectively as “The Boys of Summer.”

“Thou shalt not steal. I mean defensively. On offense, indeed thou shall steal and thou must.”

VAN LINGLE MUNGO (1911-1985): Played for the Dodgers from 1931 to 1941. Today, Van Lingle Mungo is famed primarily for his euphonious name. Prior to an arm injury that stalled his career, Van Lingle Mungo averaged 16 wins per season and led the National League in strikeouts (236) in 1936. Van Lingle Mungo was a ladies’ man and once had to be smuggled out of a hotel hidden in a laundry cart to avoid being shot by an outraged husband. Given that there’ll probably never be another Van Lingle Mungo in baseball (or anyplace else), he deserves an Honorable Mention.

VAN LINGLE MUNGO (1911-1985): Played for the Dodgers from 1931 to 1941. Today, Van Lingle Mungo is famed primarily for his euphonious name. Prior to an arm injury that stalled his career, Van Lingle Mungo averaged 16 wins per season and led the National League in strikeouts (236) in 1936. Van Lingle Mungo was a ladies’ man and once had to be smuggled out of a hotel hidden in a laundry cart to avoid being shot by an outraged husband. Given that there’ll probably never be another Van Lingle Mungo in baseball (or anyplace else), he deserves an Honorable Mention.

LEO “THE LIP” DUROCHER (1905-1991): Leo was notorious. When he was a Yankee, the man once stole Babe Ruth’s watch, an act of larceny which would have earned him a small footnote in baseball history, whatever else he ever did. Leo, however, was marked out for even greater infamy. He routinely passed bad checks to cover his gambling debts, associated with known mobsters, seduced Hollywood stars and starlets (including his wife, Laraine Day, who was married to someone else when she married him), and was responsible for bringing the staid world of baseball into contact with the glitzy world of Hollywood, an association from which the game has never recovered. Foul-mouthed and volatile, Durocher was routinely ejected (95 times!) from games for swearing at or threatening the umpires. Aside from all the drama, Leo was a talented manager who demanded the best from his players and got it. He greeted the announcement of (and the objections to) Jackie Robinson’s appointment to the Dodgers with the immortal words, “I don’t care if he’s black. I don’t care if he’s yellow. I don’t care if he’s a #&@! zebra. I’m the manager of this team and if I say he plays, he plays!” Leo, however, didn’t get to oversee Jackie’s first, difficult, year (this might not have been a bad thing, in retrospect!) as he was suspended from the game for the 1947 season, “for conduct detrimental to baseball.” Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler bowed to pressure from Larry MacPhail (who then owned the Yankees, and probably owed Leo for gambling debts), and the powerful hierarchy of the New York Diocese of the Catholic Church, who found Leo’s behavior, particularly his sinful marriage, threatening to the morals of Catholic youth. Leo returned to manage the Dodgers in 1948, but then committed the truly mortal sin of traveling uptown in 1949 to manage the Giants. Now, that’s just wrong.

Durocher with his wife, actress Laraine Day; Durocher discovers the ultimate power hitter in Herman Munster; Leo The Lip at work doing what he done best; Leo in living color.

CASEY “THE OLD PROFESSOR” STENGEL (1890-1975): Stengel is remembered chiefly for bringing the Yankees to five consecutive World Championships, mostly against the Dodgers, and his management of the Mets (“Does anybody here know how to play baseball?”), and for his “Stengelese”—“Never make predictions, especially about the future,” and “Son, we’d like to keep you around this season but we’re going to try and win a pennant,” and “There comes a time in every man’s life, and I’ve had plenty of them,” are just three of his colorful quotes. Nonetheless, Casey (then “K.C.” for his hometown of Kansas City), began his career as a player for the Dodgers (1912-1917). He wasn’t a remarkable player by any stretch, but he was popular for keeping the crowds entertained. Once, he doffed his cap to the crowd as he took up his batting stance, allowing a captive bird to fly off his head. It’s said that he convinced the pilot to substitute a grapefruit for a baseball when Wilbert Robinson tried to make a catch dropped from an overflying plane. Casey might have saved Uncle Robbie’s life. The grapefruit hit him in the head, which splattered the grapefruit. Had it been a baseball it might have splattered Robinson’s brains. Although Stengel worked to defeat the Dodgers, he was fond of recalling his Dodger playing days: “Sure I played. Did you think I was born at the age of 70 sitting in a dugout trying to manage guys like you.”

CASEY “THE OLD PROFESSOR” STENGEL (1890-1975): Stengel is remembered chiefly for bringing the Yankees to five consecutive World Championships, mostly against the Dodgers, and his management of the Mets (“Does anybody here know how to play baseball?”), and for his “Stengelese”—“Never make predictions, especially about the future,” and “Son, we’d like to keep you around this season but we’re going to try and win a pennant,” and “There comes a time in every man’s life, and I’ve had plenty of them,” are just three of his colorful quotes. Nonetheless, Casey (then “K.C.” for his hometown of Kansas City), began his career as a player for the Dodgers (1912-1917). He wasn’t a remarkable player by any stretch, but he was popular for keeping the crowds entertained. Once, he doffed his cap to the crowd as he took up his batting stance, allowing a captive bird to fly off his head. It’s said that he convinced the pilot to substitute a grapefruit for a baseball when Wilbert Robinson tried to make a catch dropped from an overflying plane. Casey might have saved Uncle Robbie’s life. The grapefruit hit him in the head, which splattered the grapefruit. Had it been a baseball it might have splattered Robinson’s brains. Although Stengel worked to defeat the Dodgers, he was fond of recalling his Dodger playing days: “Sure I played. Did you think I was born at the age of 70 sitting in a dugout trying to manage guys like you.”

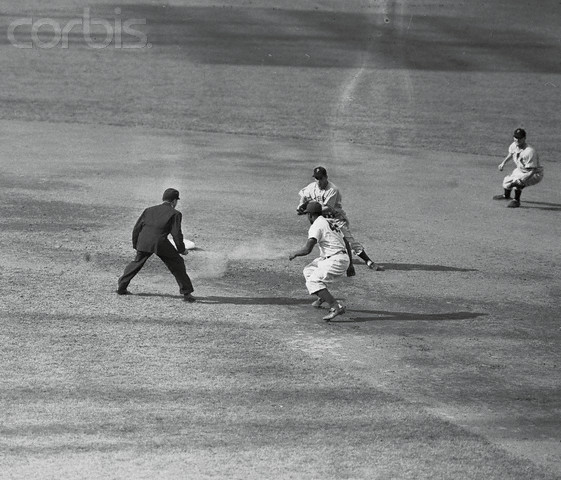

CAL ABRAMS (1924-1997): Cal, who played for the Dodgers from 1949 to 1952 was one of the supporting players during the great era of The Boys of Summer. Cal is famous mostly for losing a Pennant, but it wasn’t his fault. In 1950 the Dodgers tied for the Pennant, and faced the Philadelphia Phillies in a single-game playoff to determine who would represent the National League in that year’s World Series. In the bottom of the 9th inning, with nobody out and the game tied 1-1, Abrams was on second base when Duke Snider hit a single to short center field. Abrams was waved home by third base coach Milt Stock. Abrams, who was not noted for his speed, was out at the plate by a mile on a perfect throw by Phillies center fielder Richie Ashburn, who had fielded the ball on one bounce. The play resulted in the preservation of the 1-1 tie. Dick Sisler’s 10th inning home run ended the Dodgers’ hopes for that season. Stock was fired after the season for his decision to wave Abrams home.

CAL ABRAMS (1924-1997): Cal, who played for the Dodgers from 1949 to 1952 was one of the supporting players during the great era of The Boys of Summer. Cal is famous mostly for losing a Pennant, but it wasn’t his fault. In 1950 the Dodgers tied for the Pennant, and faced the Philadelphia Phillies in a single-game playoff to determine who would represent the National League in that year’s World Series. In the bottom of the 9th inning, with nobody out and the game tied 1-1, Abrams was on second base when Duke Snider hit a single to short center field. Abrams was waved home by third base coach Milt Stock. Abrams, who was not noted for his speed, was out at the plate by a mile on a perfect throw by Phillies center fielder Richie Ashburn, who had fielded the ball on one bounce. The play resulted in the preservation of the 1-1 tie. Dick Sisler’s 10th inning home run ended the Dodgers’ hopes for that season. Stock was fired after the season for his decision to wave Abrams home.

Abrams befriended Jackie Robinson. Cal was sensitive to instances of racism, and particularly anti-Semitism of which there were many in professional baseball at that time. Jewish players were routinely called “Abie” or “Moses,” and were sometimes subjected to humiliating treatment. Dodger manager Charlie Dressen refused to let him play on “Cal Abrams Day” at Ebbets Field in 1951. In 1952, he was traded away. The story is told that Dressen ordered Cal to bench jockey Reds manager Rogers Hornsby. Cal then needled, insulted and mocked Hornsby throughout the entire game, enraging him. During the break between the first and second games, Abrams was told he had been traded—to the Reds.

Abrams considered his time with the Dodgers to be the most meaningful of his baseball career and loved the team. When he died in Florida in 1997 he was buried in his Brooklyn Dodgers uniform.

RED BARBER (1908-1992): Walter Lanier “Red” Barber was born in Mississippi, and though he broadcast games for the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1939 to 1953, never lost the distinctive Southern drawl which became his trademark. Barber broadcast the sport’s first televised contest on August 26, 1939 in Brooklyn.

RED BARBER (1908-1992): Walter Lanier “Red” Barber was born in Mississippi, and though he broadcast games for the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1939 to 1953, never lost the distinctive Southern drawl which became his trademark. Barber broadcast the sport’s first televised contest on August 26, 1939 in Brooklyn.

“The Ole Redhead” was known for his warm, honey-slow and folksy delivery, and brought many country colloquialisms to the lips of Brooklynites. The Dodgers were “in the catbird seat” when they were winning; baseball arguments and bench-clearing incidents were “rhubarbs;” Ebbets Field was “the rhubarb patch;” a close game could be “tighter than a new pair of shoes on a rainy day,” but by contrast, a team with an overwhelming lead would have the game “tied up in a croker sack.” Barber was also literate: He could describe a stranded runner by saying that his teammates had “left him languishing there like the Prisoner of Chillion,” referencing a poem by Lord Byron.

After Red Barber moved on sixty years ago in 1949 he was replaced by Vin Scully who still calls games for Los Angeles.

A Brooklyn fan out walking in the summer streets didn’t need a radio since he could hear Barber’s running commentary as he passed every open window on the street, “the voice of the Brooklyn Dodgers.”

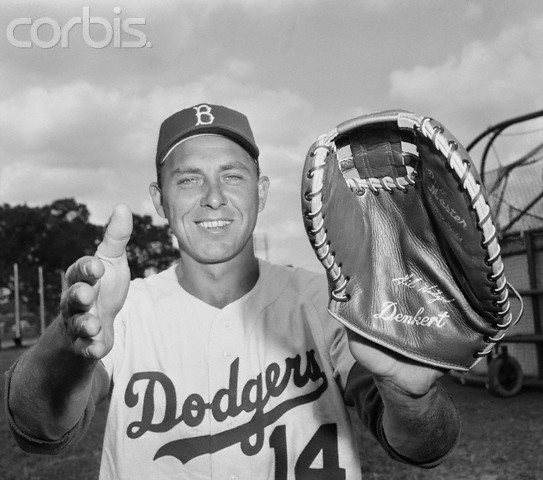

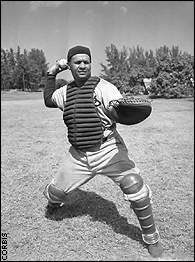

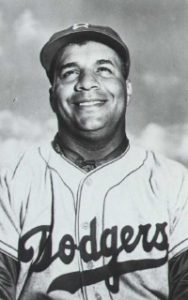

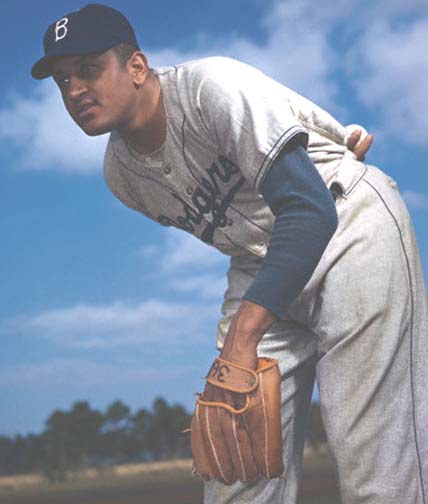

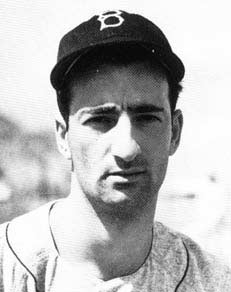

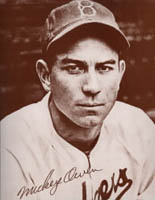

MICKEY OWEN (1916-2005): Like Cal Abrams, Mickey is remembered for a classic Dodgers disaster. More than likely, it might have cost the Dodgers the 1941 World Series. Although the mistake did not come in the deciding game, its psychological impact on the team undoubtedly affected them. The Bums were playing the Yankees (for the first, but not, oh no, not for the last time). During the 1941 season, Owen had set a record for most errorless fielding chances by a catcher with 508 perfect attempts and finished with a .995 average. The near-flawless Owen earned his place in baseball lore for the costly passed ball that came in the 9th inning of Game Four of the ’41 World Series. The Yankees held a 2-games-to-1 lead entering Game 4 at the Dodgers’ home field, Ebbets Field, but with 2 outs in the top of the ninth inning and the count 3-2 on the Yankee’s Tommy Henrich the Dodgers led 4-3. Henrich swung and missed at strike 3 which would have been the final out, but Owen muffed the catch for the only error of the game. Henrich made it safely to first base. The heart of the Yankee order, including DiMaggio, then went on to rally to score four runs in that inning and held on to win the game 7-4. Instead of the series being even at 2-2 the victory gave the Yankees a 3-1 lead in the series and, the next day, New York beat the Dodgers 3-1 in Game 5 and won the World Championship.

MICKEY OWEN (1916-2005): Like Cal Abrams, Mickey is remembered for a classic Dodgers disaster. More than likely, it might have cost the Dodgers the 1941 World Series. Although the mistake did not come in the deciding game, its psychological impact on the team undoubtedly affected them. The Bums were playing the Yankees (for the first, but not, oh no, not for the last time). During the 1941 season, Owen had set a record for most errorless fielding chances by a catcher with 508 perfect attempts and finished with a .995 average. The near-flawless Owen earned his place in baseball lore for the costly passed ball that came in the 9th inning of Game Four of the ’41 World Series. The Yankees held a 2-games-to-1 lead entering Game 4 at the Dodgers’ home field, Ebbets Field, but with 2 outs in the top of the ninth inning and the count 3-2 on the Yankee’s Tommy Henrich the Dodgers led 4-3. Henrich swung and missed at strike 3 which would have been the final out, but Owen muffed the catch for the only error of the game. Henrich made it safely to first base. The heart of the Yankee order, including DiMaggio, then went on to rally to score four runs in that inning and held on to win the game 7-4. Instead of the series being even at 2-2 the victory gave the Yankees a 3-1 lead in the series and, the next day, New York beat the Dodgers 3-1 in Game 5 and won the World Championship.

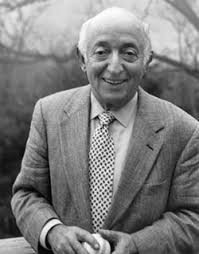

ROGER KAHN: Born in 1927, Roger is famous for his sportswriting on behalf of various publications, but he gained a measure of immortality with his semi-autobiographical The Boys of Summer. The title was lifted from Dylan Thomas’ famous poem, but Roger made it more famous, and linked the Dodgers with it forever by using it to refer to the heart of the 1950s Dodger lineup. The nickname has passed into regular English usage to refer to the Brooklyn Dodgers in general. Roger also wrote The Era—1947-1957 discussing the Yankees and Dodgers and Giants shared dominance of baseball during those eleven seasons.

ROGER KAHN: Born in 1927, Roger is famous for his sportswriting on behalf of various publications, but he gained a measure of immortality with his semi-autobiographical The Boys of Summer. The title was lifted from Dylan Thomas’ famous poem, but Roger made it more famous, and linked the Dodgers with it forever by using it to refer to the heart of the 1950s Dodger lineup. The nickname has passed into regular English usage to refer to the Brooklyn Dodgers in general. Roger also wrote The Era—1947-1957 discussing the Yankees and Dodgers and Giants shared dominance of baseball during those eleven seasons.

STAN “THE MAN” MUSIAL (b. 1920): Although Stan Musial was never a Dodger, I include him here out of respect. Not only was Musial one of the finest players the game has ever seen, and not only was he warmly regarded by all, but THE MAN owned Ebbets Field—and I mean owned it. Stan’s average inside the Pea Patch was an incredible .536!

STAN “THE MAN” MUSIAL (b. 1920): Although Stan Musial was never a Dodger, I include him here out of respect. Not only was Musial one of the finest players the game has ever seen, and not only was he warmly regarded by all, but THE MAN owned Ebbets Field—and I mean owned it. Stan’s average inside the Pea Patch was an incredible .536!

By the way, he got his nickname in Brooklyn. Brooklyn fans, a raucous bunch at the best of times, never booed THE MAN. Instead, they seemed to regard him with a kind of respectful awe as he stepped from the dugout: “Here comes THE MAN again!” And he was always “THE MAN” never “that man.” He’ll always be THE MAN. RALPH BRANCA AND BOBBY THOMSON AND THE SHOT HEARD ‘ROUND THE WORLD: Two men linked together by fate: The talented but unspectacular Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca threw a baseball at the talented but unspectacular New York Giants outfielder Bobby Thomson at 3:58 PM on October 3, 1951, a dark and gloomy day for baseball at the Giants’ Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan.

The two National League teams were the vilest of rivals and enemies, and had been so since the earliest days of the Twentieth Century. The Dodgers had squandered a 13.5 game lead and the Giants had won 36 of their last 42 games to bring the season down to a three game playoff series, split between the two teams.

In the bottom of the Ninth, the Dodgers were ahead 4-1, when things unravelled for the hapless Bums. The Giants scored on a ball that sneaked through the shallow infield. The tiring Dodger ace, Big Don Newcombe, found himself facing two Giants on base and one out.

Manager Charlie Dressen decided Newk had had it, and sent Branca up against Thomson. Dodger fans shuddered, remembering that Thomson had homered off Branca two days previously. What nobody knew was that the Giants, who had been floundering badly and then came alive late in the season, had a telescope trained on home plate and had been stealing signs for months, courtesy of their manager, the Benedict Arnold of Brooklyn, Leo Durocher. Did they steal the sign on this pitch? Who knows?

On Branca’s second pitch, Thomson connected with a spectacular shot that rocketed into the stands, shattering the Dodgers’ season, taking the pennant, and making himself one half the instrument of the most famous moment in baseball. In the picture above, Jackie Robinson, with his back to the camera, is in a posture of complete disbelief.

The crack of that bat reverberated all the way around the world, thanks to the first “live feed” cross-country television cable and thanks to Armed Forces Radio, where it momentarily drowned out the Korean War. There are famous photographs of Branca weeping. There are famous photographs of Thomson kissing his bat. It is said that suicide lines formed on the Brooklyn Bridge. Branca was hanged in effigy. To this day, there are still those who curse him.

Fortunately, Thomson and Branca are fine men who have managed to prolong their shared moment into a lifetime friendship, and goodnatured fellowship.

Yes, it was a sad moment for Brooklyn Dodger fans, but it was another chapter in the wonderful odyssey that is Brooklyn baseball.

PETE HAMILL: Pete Hamill is a novelist, essayist and journalist whose career has endured for more than forty years. He was born in Brooklyn in 1935. He has been a columnist for the New York Post, the New York Daily News, and New York Newsday, the Village Voice, New York magazine and Esquire. He has served as editor-in-chief of both the Post and the Daily News.

PETE HAMILL: Pete Hamill is a novelist, essayist and journalist whose career has endured for more than forty years. He was born in Brooklyn in 1935. He has been a columnist for the New York Post, the New York Daily News, and New York Newsday, the Village Voice, New York magazine and Esquire. He has served as editor-in-chief of both the Post and the Daily News.

Pete’s Dodger connection is visceral. As a youngster and a young man he was imbued by his family with a love of Brooklyn baseball. It was Pete and Jack Newfield who each wrote their own list of the three worst villains of the 20th century on a piece of paper to settle a discussion they were having over lunch. They wrote the same three names in the same order: Hitler, Stalin, Walter O’Malley. On December 4, 2007, Pete reacted to the election of O’Malley to the Baseball Hall of Fame in a Daily News column by speaking plainly about what the Dodgers had meant to Brooklyn, what had been lost when they left, and the role O’Malley played. It can all be summed up in his one phrase: “Never forgive. Never forget.”

ABE STARK (1893-1972): Abe started out as a tailor and haberdasher with a store at 1514 Pitkin Avenue. Next to Harry Truman, he may be the most famous haberdasher/politician in the world, for Abe advertised at Ebbets Field. His sign, right under the scoreboard, said, “Hit Sign. Win Suit.” It was not an easy challenge. The sign was low to the ground, very narrow, and placed at an odd angle to home plate. “Hit Sign. Win Suit.” became world famous through newsreels and then television, and so did Abe, who eventually became Brooklyn Borough President and then City Council President. As part of his legacy to Brooklyn he helped found the Brownsville Boys Club, which yours truly attended as a preschool. Most stadiums have adopted some variation on Abe’s marketing plan to pique fan interest. And, oh yeah, only a few suits ever had to be given away over the years. It pays to advertise.

ABE STARK (1893-1972): Abe started out as a tailor and haberdasher with a store at 1514 Pitkin Avenue. Next to Harry Truman, he may be the most famous haberdasher/politician in the world, for Abe advertised at Ebbets Field. His sign, right under the scoreboard, said, “Hit Sign. Win Suit.” It was not an easy challenge. The sign was low to the ground, very narrow, and placed at an odd angle to home plate. “Hit Sign. Win Suit.” became world famous through newsreels and then television, and so did Abe, who eventually became Brooklyn Borough President and then City Council President. As part of his legacy to Brooklyn he helped found the Brownsville Boys Club, which yours truly attended as a preschool. Most stadiums have adopted some variation on Abe’s marketing plan to pique fan interest. And, oh yeah, only a few suits ever had to be given away over the years. It pays to advertise.

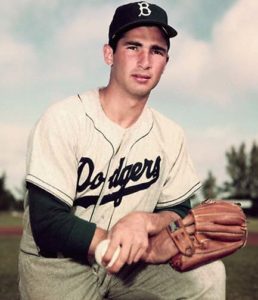

SANDY KOUFAX: Sandy, Brooklyn-born and Brooklyn-raised was a member of the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers World Championship team. He is, arguably (though you’d get no argument from me), the greatest pitcher in baseball history. And even though his great years came after the Brooklyn Dodgers were gone, he deserves a spot on this list. You gonna argue with me? Don’t even think about it, okay? I’m from BROOKLYN!

WILLARD MULLIN (1902-1978): Willard was a well-known and widely-published sports cartoonist who invented the Brooklyn Bum. Supposedly, the idea came to him during a taxi ride when the cabbie asked, “How’s dem bums doin’ today?” In Brooklyn, there was no question who he meant.

JACKIE MITCHELL (1914-1987): Mitchell was taught to pitch by her neighbor, Dazzy Vance. As a female pitcher, Virne Beatrice Mitchell was another Dodgers “first.” Although Jackie never got a chance to play for the big club itself, she is renowned as “The Girl Who Struck Out Babe Ruth.” On April 2, 1931, when Jackie was just seventeen, the Yankees played an exhibition game against the Dodgers’ AA Minor League farm club, the Chattanooga Lookouts, with Jackie on the mound. Jackie struck out The Babe on four pitches (a ball and three strikes); she then immediately faced Lou Gehrig, who went down after three called strikes (nonetheless, the Yankees won, 14-4). The New York Times duly noted the accomplishment (and also reported that the “Robins” had lost to the Yankees’ AAA Hartford affiliate 5-2 that same day). Having awed all of professional baseball by striking out two of its greatest players on seven pitches, Jackie was rewarded by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis by having her contract voided, essentially banning her from playing pro ball ever again.

JACKIE MITCHELL (1914-1987): Mitchell was taught to pitch by her neighbor, Dazzy Vance. As a female pitcher, Virne Beatrice Mitchell was another Dodgers “first.” Although Jackie never got a chance to play for the big club itself, she is renowned as “The Girl Who Struck Out Babe Ruth.” On April 2, 1931, when Jackie was just seventeen, the Yankees played an exhibition game against the Dodgers’ AA Minor League farm club, the Chattanooga Lookouts, with Jackie on the mound. Jackie struck out The Babe on four pitches (a ball and three strikes); she then immediately faced Lou Gehrig, who went down after three called strikes (nonetheless, the Yankees won, 14-4). The New York Times duly noted the accomplishment (and also reported that the “Robins” had lost to the Yankees’ AAA Hartford affiliate 5-2 that same day). Having awed all of professional baseball by striking out two of its greatest players on seven pitches, Jackie was rewarded by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis by having her contract voided, essentially banning her from playing pro ball ever again.

HAPPY FELTON (1907-1964): No one is absolutely certain what Happy Felton’s real name was. A successful bandleader and musician in the 1930s, Felton changed his name several times throughout the years. Though he was always known as a supremely jovial man, Felton was profoundly unhappy much of the time, developing an eating disorder that ended his life prematurely. In the 1950s, Happy Felton had a pre-game show at Ebbets Field called Happy Felton’s Knot Hole Gang. The show aired about a half hour before game time. Three Little Leaguers would appear on each show, along with a Dodger who would work them out and decide who among them was the better player. The winner could get to come back the next day and talk to the player of his choice just before the game started. Happy Felton also had a post-game show, Talk to the Stars. He would interview the two top players of the day. Suggested questions were sent in by fans, and Happy and his staff would choose a fan question for each show. The participating players would receive $50.00 for appearing on either the pre-game show or post-game show. Pee Wee Reese appeared so many times that the Dodgers joked that he was still cashing checks into his eighties!

HAPPY FELTON (1907-1964): No one is absolutely certain what Happy Felton’s real name was. A successful bandleader and musician in the 1930s, Felton changed his name several times throughout the years. Though he was always known as a supremely jovial man, Felton was profoundly unhappy much of the time, developing an eating disorder that ended his life prematurely. In the 1950s, Happy Felton had a pre-game show at Ebbets Field called Happy Felton’s Knot Hole Gang. The show aired about a half hour before game time. Three Little Leaguers would appear on each show, along with a Dodger who would work them out and decide who among them was the better player. The winner could get to come back the next day and talk to the player of his choice just before the game started. Happy Felton also had a post-game show, Talk to the Stars. He would interview the two top players of the day. Suggested questions were sent in by fans, and Happy and his staff would choose a fan question for each show. The participating players would receive $50.00 for appearing on either the pre-game show or post-game show. Pee Wee Reese appeared so many times that the Dodgers joked that he was still cashing checks into his eighties!

THE BOYS OF SUMMER

One of the things that made the Dodgers such an effective team was the deep sense of cohesion shared between the men on the field, a sense that extended into the stands at Ebbets Field, and on into the streets of Brooklyn, and beyond. No other team has ever had the bond that Dem Bums had with Brooklyn, and a lot of it started right on that impossibly green diamond. Unlike modern baseball, where obscene amounts of money and free agency have utterly changed the tenor of the game, baseball as played by the Boys of Summer had a quality of purity. They certainly didn’t play for the money. Jackie Robinson made the league minimum of $5,000.00 for the season when he came to Brooklyn in 1947. Don Zimmer’s original salary was $140.00 per month. And even though a big star like Duke Snider might make a five figure salary, good money for the Fifties, it certainly wasn’t enough to give a man airs. They lived in little houses on little plots of land in tree-lined Bay Ridge, many of them, and carpooled to work, where they parked their cars in a special lot set aside for them by the owner of the Mobil station across the street. Before work, they signed autographs for the flocks of fans—children and adults—who mobbed them at batting practice. None of them ever charged for an autograph. They participated gladly, and for an extra $50.00, in the Dodgers pregame TV show, Happy Felton’s Knothole Gang, where lucky kids might get to toss a ball with Pee Wee Reese or Carl Furillo. Louis Gossett Jr. tells the story of how he was shocked into speechlessness when Jackie Robinson picked him out for a game of catch.

What made the Brooklyn Dodgers OUR Dodgers was the fact that these guys not only worked together, lived together and played together on the street where we lived—They stayed together. From 1947 to 1957 the names Robinson, Reese, Hodges, Snider, Erskine and Furillo seemed to be engraved on the very air in Brooklyn. Permanence. Solidity. Dependability. (Okay, so we could always depend on blowing the Pennant on the last day of the regular season, or, if not, losing the Series in seven to the Yankees.) Ebbets Field was a magical place, where Hilda Chester and the Sym-Phony could exist and Billy Loes could lose a ground ball in the sun. People prayed for Gil Hodges when he went into a devastating batting slump—It worked. Imagine anybody praying for A-Rod today. Every moment in Dodger Time was evanescent and utterly unique. Still, it was as though it would never end. And in a way, it hasn’t.

Was it a perfect world? Of course not. Red paranoia was destroying lives. The atom bomb was a real-world reminder of all our anxieties. Yes, Jackie had come, and Campy, and Newcombe, and Joe Black, but for the most part, African-Americans lived under a system of institutionalized repression that was designed to break a man, body and spirit. What touches me most about Pee Wee’s now-famous gesture toward Jackie is that it was not a political act. Pee Wee wasn’t thinking that this was his moment to make history. No. Pee Wee saw a man in trouble—not a black man, not a white man, just a man—and instinctively gave him support. Harold Henry Reese was not a firebrand, not a philosopher, not a liberal, certainly not a revolutionary. He was just a good man reaching out toward another good man in need. Storytellers say that it happened in Cincinnati, but that’s almost too convenient—right across the river from Pee Wee’s native Louisville, with his friends and neighbors in attendance. No, nobody knows where it actually happened, and in all truth that is all right. It happened in America.

- They won the Series at last. They had their moment in the sun. And then they were gone.