The Unyielding Spirit

In my first year of college, I was introduced to a form of sitting meditation by one of my Professors, Rajah Singh, the hereditary Court Musician of the Mogul Emperors of India. Although Rajah Singh did not call what he was teaching us “Zazen,” that was in fact what it was. ~ This experience led me into a long, if intermittent, apprenticeship as a Zen practitioner, occasionally as a visitor to a sitting group, but most often alone. ~ Without a formal teacher, my hither-and-yon education in Zen was punctuated primarily by reading authors such as Alan Watts, Peter Matthiessen, D.T. Suzuki and Shunryu Suzuki. ~ I drifted away from Zen in the 1990s and early 2000s, focusing more intently on developing my legal practice. ~ Some years ago, I reintroduced myself to Zen practice under the tutelage of Doshin Cantor Sensei and my Dharma family at the Southern Palm Zen Group in Boca Raton, Florida. ~ To them this page is dedicated in respect, reverence, and deepest affection. ~ Gassho. Zen traces its earliest roots back to the intense sitting meditation practiced by the Buddha which resulted in his enlightenment. “Zen” is a Japanese word transcribed from the Chinese “Ch’an,” which in turn derives from the Sanskrit word “Dhyana.” It is also known as “Thien” in Vietnam and “Son” in Korea. Zen is spare. It puts aside the iconography and ritual of other forms of Buddhism, focusing on the practitioner’s direct experience of this present moment…

Zen traces its earliest roots back to the intense sitting meditation practiced by the Buddha which resulted in his enlightenment. “Zen” is a Japanese word transcribed from the Chinese “Ch’an,” which in turn derives from the Sanskrit word “Dhyana.” It is also known as “Thien” in Vietnam and “Son” in Korea. Zen is spare. It puts aside the iconography and ritual of other forms of Buddhism, focusing on the practitioner’s direct experience of this present moment…

Where Did Zen Come From?

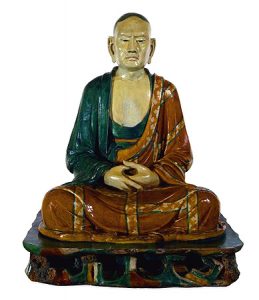

Zen traces its putative beginnings back to the day the Buddha sat in meditation under the Bodhi Tree all those years ago. In India, the sitting practice was known as Dhyana. Dhyana was carried from India to China by Bodhidharma two millennia later, and developed in China as Ch’an, which was then brought to Japan as Zen by Master Eisai. Zen also traveled to Korea, where it is known as Son, and to Vietnam, where it is called Thien. Around 1500, Zen became a major influence on Japanese culture, inspiring calligraphy, art, gardening, the Tea Ceremony, and other traditional Japanese activities. Zen was adopted by the Imperial Court, and became the prime philosophy of the Samurai.

Zen did not reach the West until after Japan was opened by Commodore Perry in 1853, and it put down very shallow roots for the next century as the esoteric practice of a very few Westerners. The first Japanese Zen Master, Soyen Shaku, arrived in America in 1893. Zen only really began to grow in t he Occident in the Twentieth Century, when academics like Christmas Humphreys, Reginald Blyth, Lafcadio Hearn, Ruth Fuller Sasaki, Gary Snyder, and Alan Watts began writing about it in books and in the popular press. The Platform Sutra was translated into English for the first time in 1930, the same year that Sokei-an Sasaki established the First Zen Institute of the United States. The end of the Second World War, and the return of American soldiers from Occupied Japan, brought an upsurge of interest in Zen. Eugen Herrigel wrote “Zen In The Art of Archery” in 1953. Jack Kerouac published “The Dharma Bums” in 1959, and Watts’ prolific pen continued spawning new writings until his death in 1973.

In 1950, D.T. Suzuki, a transplanted Japanese Zen student of Soyen Shaku began writing incisive (though intellectual) popular books on Zen. Despite his very linear Western approach to Zen, “Big” Suzuki sowed fertile ground for “Little” Suzuki, Shogaku Shunryu Suzuki, who arrived in San Francisco in 1958, creating the San Francisco Zen Center, an open-door Zendo, where anyone interested in Zen could come and sit, listen to lectures, and immerse themselves in active, daily Zen practice. In the experimental and freewheeling era of the 1960s, Zen grew rapidly. Shunryu Suzuki established the first U.S. Zen monastery in 1967, at Tassajara. In 1970, his seminal “Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind” was published.

Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi arrived in Los Angeles in 1956, and established the Zen Center of Los Angeles in 1967. His resulting lineage, The White Plum Asanga, is one of the largest Zen groups in the West, and has branches in Europe, the Americas, and Israel.

Other important Zen teachers in the West include Dainan Katagiri, whose Asanga is primarily Midwestern; Yasutani Hakuun, who founded the Three Treasures Association in Japan and ordained Western Zen Masters to teach in America; and the Americans Bernie Tetsugen Glassman, Charlotte Joko Beck, Tenshin Reb Anderson, Jakusho Kwong, Robert Aitken Roshi, Joan Jiko Halifax Roshi, Robert Kennedy Roshi, S.J., Daigaku Rumme, and Gerry Shishin Wick. Many of the teachers have founded organizations, like Glassman’s Zen Peacemakers Order, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, and networks of Settlement Houses in poorer areas.

Although most of these teachers can trace their lineages back to either Suzuki Roshi or Maezumi Roshi, one of the hallmarks of American Zen is its flexibility. Teachers from different lineages work together freely, liturgy and practice are both shared and improvisational, and teachers easily found their own schools and lineages. Thus, American Zen is a colorfully tangled tapestry of creative thought, mindful living, and social action.

Who Was The Buddha?

What most people don’t realize is that the word “Buddha” is not a name, but a description. Like the word “budded,” to which it is etymologically related, it connotes a awakened state.

Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha, was born 2,500 years ago in the northern Indian city of Kapilavastu. He was a prince of the Shakya Clan, and is therefore often referred to as the Buddha Shakyamuni. At the age of thirty, Shakyamuni left his pampered life, and set out across India, seeking to understand the nature of human existence—really to find himself. Over the next six years, Shakyamuni practiced various disciplines, both ascetic and indulgent. Frustrated by this seemingly endless, answerless life of seeking without finding, he declared that he would sit in meditation either until he became enlightened or he died trying. Enlightenment came with the dawn. It is said that when he perceived the morning star he intuited the singularity that is all existence.

Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha, was born 2,500 years ago in the northern Indian city of Kapilavastu. He was a prince of the Shakya Clan, and is therefore often referred to as the Buddha Shakyamuni. At the age of thirty, Shakyamuni left his pampered life, and set out across India, seeking to understand the nature of human existence—really to find himself. Over the next six years, Shakyamuni practiced various disciplines, both ascetic and indulgent. Frustrated by this seemingly endless, answerless life of seeking without finding, he declared that he would sit in meditation either until he became enlightened or he died trying. Enlightenment came with the dawn. It is said that when he perceived the morning star he intuited the singularity that is all existence.

Following his enlightenment, Shakyamuni spent the next fifty years wandering throughout India teaching others what he had learned. These people became the foundation of the Sangha, the Buddhist community. Today the extended Sangha exists throughout the world, with large populations in Ceylon, Burma, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Korea, Mongolia, China, Nepal, Bhutan, Japan and Tibet, as well as smaller but vital groups in India, Europe and the Americas.

There is no one Buddhist dogma. Instead, Buddhism has developed hundreds of divergent branches. All Buddhists ascribe to the “Four Noble Truths” and “The Eightfold Path” and to some version of the Buddhist Precepts, but the forms of Buddhist practice are almost as numerous as the Sangha itself. Although many of the various Buddhist sects have woven colorful legends around him, there was nothing supernatural, divine, or magical about the Buddha. He was a mortal man who lived about eighty years and died of food poisoning, a quite ordinary occurrence in ancient Asia.

At most, and this is much, it can be said that the Buddha “got it,” that he was one of those individuals who lived every moment of his life, that he was aware and mindful of himself, of others, and of everyone and everything’s place in this world. If Zen practice can be said to have any point it is to live life in that manner.

Soto? Rinzai? Or Doesn’t It Matter?

Zen practitioners belong to a number of different “schools,” each of which maintains its own traditions of ritual, liturgy, and approach to practice. The two major schools are “Rinzai” (named for it’s founder) and “Soto” (named for it’s two founders, Sozan and Tozan). Both schools use Zazen and Koans in their teaching, though Rinzai uses more Koan study and Soto more Zazen. Rinzai is frequently known as the “sudden enlightenment” school, while Soto is known as the “gradual enlightenment” school. Some lineages, such as the White Plum Asanga, have antecedents in both schools.

Is Zen A Religion?

This is one of the most common questions I come across. Certainly Zen, like other Buddhist sects, has a liturgy, a formal priesthood, and a congregational structure. But significantly, there is no one answer every Buddhist (Zen or otherwise) will give to questions about, life, death, a deity, reincarnation, vegetarianism, or even the Buddha himself. Unlike Christianity, Buddhism does not consider its founder to be more than human. Unlike Islam, Buddhism does not consider the message of its founder to be the ultimate revelation. Unlike Judaism, Buddhism makes no assertions as to the nature of God and His relationship with Man. There is no Holy Writ. Buddhists recognize the validity of their texts as guides to right living, but they also recognize that sutras and stories about the Buddha are not historical documents. And Zen goes further than most Buddhist sects in jettisoning iconography and liturgy. The old Zen Masters were wont to tell their students, “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him!” and to burn wooden statues of the Buddha to keep warm in their chilly Zendos. Symbols have meaning, but only as symbols. Zen addresses the present moment, and Zen training is all focused on living fully in the present in a meaningful and ethical way as expressed in the Precepts. Meaning and ethics are found through quieting the “monkey mind,” that small, angst-ridden, past and future obsessed and infinitely selfish chatterbox inside our heads. As our inner dialogue, wants and fears subside, we are able to live more fully in the present without anxiety and distraction. The methodology of calming the monkey mind and of opening oneself to the present is Zazen.

Western Zen does maintain some traditional Japanese forms, having come from that country. Participation in Sangha activities, adoption into a lineage, and ordination ceremonies are important symbolic wayposts for the dedicated practitioner, and as indicators of the student’s depth of commitment. There is, however, nothing that precludes a Zen practitioner from maintaining an active relationship with, or even a religious office within, another tradition. Zen practice and living by the Precepts may deepen a person’s spiritual life, but dedication to Zen practice is no more “religious” than an equal dedication to the study of the martial arts.

Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, Karma

These are terms that recur repeatedly in Buddhist practice of all types. Each one of these words has multiple meanings. One Buddhist scholar notes that there are 40 (!) separate definitions for “Dharma” alone. Even the term “Buddha” evades easy definition. The word means “Awakened,” and it, of course, is the title given to to that Prince of the Shakya kingdom who sat under the Bodhi Tree seeking Enlightenment. But the Buddha is not the only Buddha there is. Many Buddhist schools revere other Buddhas alongside Siddhartha Gautama. According to certain schools of Buddhism (including Zen) we are all Buddhas and the universe is an expression of Buddha nature.

“Dharma” is even less easy to grasp. In it’s most concrete sense, the Dharma is the teachings of the historical Buddha, but Dharma can also be used to describe any positive sharing between individuals. It can also refer to the natural rhythm of existence. And, as might be expected of a word with so many shades of meaning, some of them are undeniably subtle.

The “Sangha” is the community, usually meaning the membership of one’s own Zendo or monastery, but it can also refer to the Buddhist population as a whole, and by even further extension, the entirety of the human family. Together with Buddha and Dharma, Sangha is one of the Three Treasures of Buddhism.

“Karma” means “action,” and depending upon one’s point of view, Karma may be a system of retribution and reward for prior acts, or it may simply refer to an individual’s working out of his own life’s path, or the world’s fate. People often speak of “good Karma” or “bad Karma” or even “instant Karma.” The thing to remember is that none of these definitions excludes any of the others.

“Enlightenment” is that state of existence reached by the Buddha. Exactly what Enlightenment entails is hard to say. It is certainly not some superhuman condition. According to Zen, we are all already Enlightened, though we are not usually aware of the fact. In our unaware state we often act in ways counter to the behavior inherent in our Enlightened selves. Despite being Enlightened, there’s no doubt that the Buddha had head colds, aches and pains, and cranky days. He aged and died quite normally. It was the manner in which he addressed the conditions of his life which made him Enlightened. In Japanese, a “breakthrough” moment of Enlightenment (which we all have) is called kensho. Closely related is satori, the condition of Enlightenment. And when we practice Zazen and quiet our minds, we are experiencing samadhi, a kind of pre-Enlightened state of receptivity. Other students of Zen might define these terms radically differently, but in my own practice these are the working definitions which I feel are most meaningful to me.

The First Noble Truth: An Ordinary Day

Western scholars and philosophers have usually translated the First Noble Truth as “All Life is Suffering.”

However, the Sanskrit word “Dukkha” can also be translated as “unease,” “discomfort,” or “dissatisfaction.” Mick Jagger said it best: “I can’t get no satisfaction.”

In Sanskrit itself, “Dukkha” literally refers to the “stuckness” of a cart wheel in mud . . .

Now imagine it’s today.

It’s right now and our car is mired up to the axles in mud, four wheel drive notwithstanding. Not only can you and I get nowhere, but time is passing, darkness is falling, we need to get where we’re going, and, to be honest, we just want to go home.

How much brute force is it going to take just to move the car out of the mud? Maybe I’m annoyed because I told you to make a left back there and you didn’t. Or maybe you did, and now you’re annoyed at me. The kids are crying. I have to “go,” real bad. Thanks alot, Einstein. And it could be worse; it could be raining. We might fall face first into the mud in all our floundering around. Wonderful.

What a job it’s going to be first emptying the trunk, making sure our stuff doesn’t get muddy, and then reloading it all afterward so we can get on our way. Chances are that beside the jack, the spare and a few tools, the rest of the stuff in the trunk shouldn’t even be in there: “Why didn’t you take the dry cleaning into the house?”

“Since when is that my job? It’s your stuff.”

By the end of it all, we’re going to be dirty, tired, uncomfortable, sore, bruised, and angry — Angry at ourselves for taking the muddy road (especially if we already had some idea that the road might get muddy), angry at the County for not fixing the road — what are they doing with all that tax money, anyway? — angry with the what and who and why of being out on the road, and angry with each other.

Not to mention that my boss might be angry because I’m late again or your mother’s angry because we missed picking her up for your sister’s wedding.

And so far we’re only up to the First Noble Truth!

Now imagine . . . In our story nothing really bad has happened to us. This is just an inconvenience. That’s an awful amount of exertion—exertion to the point of exhaustion—considering that

Nothing happened!

The Second Noble Truth: Gimme Dat, Gimme Dat, Gimme, Gimme, Gimme Dat, Gimme Dat Ding

Western scholars and philosophers have usually translated the Second Noble Truth as “The Cause of Suffering Is Craving.”

It’s just a fancy way of saying that we make ourselves nuts when we want what we can’t get.

Think about it. Especially in our Western culture we are completely hung up on getting more stuff.

“Gee, I really want a flat screen TV. A sixty-inch. And TiVo. What’s the point of getting a TV without TiVo? Oh, yeah, we might as well get a Blu-ray while we’re at the store. We’re gonna need a new TV stand for the TV. And it’s gotta match the furniture we already have. And, boy, am I dumb, but we’ll have to replace the DVDs with Blu-ray discs, at least a couple at first. I know we just bought “Quantum of Solace” on regular disc, but I’ve got to have my James Bond! Should we call up and check on satellite TV?

Of course we’ll get something out while we’re shopping. Chinese? Mexican? How ’bout that new steakhouse that just opened? I hear they carry Brooklyn Brown Ale.

Yes, we’ll have two New York strips with garlic mashed potatoes and —Green beans, hon?— She’ll have green beans. I’ll have peas.

Dessert? Nah, I’m stuffed. You too? No dessert; just the check please.

What do you mean my credit card’s been declined???“

Boy, what an evening! We just bought about $2,000 worth of electronics that will be obsolescent in about three months, we’ve got bills to pay, which means work, work, work, thank you very much, we’ve eaten a heavy dinner which is making my bowels growl, and now we suddenly realize we’ve tapped ourselves out. Lucky we have that other card. That’s also been declined? Didn’t you pay the bill? Look, it was your idea to buy this junk, it was your idea to go out to eat — I know you’re just full of lousy ideas. Wasn’t it your idea to get married in the first place?

By the time the argument’s over, one of us is going to be sleeping on the couch. We’re probably going to fight over that because that new big TV is in the living room. Does it never end?

Not really, if we stay stuck on craving. And it doesn’t just have to be material things. Even craving for something as altruistic as World Peace can be a problem, because we aren’t going to get it. Damn those guys in Stanannistan! Why don’t they get it? World Peace, man!

Basically, everything is craving. Even going to the Zendo to meditate can be a trap if I walk in there thinking that meditation is going to give me peace of mind. It’s like saying, “Don’t think about peppermint candy-striped elephants.” Calm my mind? Yadda, yadda, yadda. Why can’t I turn this off? Aaargh! Isn’t that the point of coming here?

Not really. The point is that there is no point to sitting beyond the actual act of sitting itself. If I sit with a goal in mind then I’m craving, desiring that goal or outcome. I’m still stuck on the wheel, still living out my Karma. That’s human life. Even the Buddha wept when he heard the news that his native land had been invaded and conquered by its enemies.

Is there any such a one as a fully enlightened one?

The Third Noble Truth: Do I Need This?

The Buddhist philosophers say that the Third Noble Truth is translated as “The extinguishment of suffering is the extinguishment of craving.” It works the other way around, too. That’s a mouthful for certain. I’ve heard someone else describe it as “Suffering can be beaten.” I don’t like that one. Something about “suffering” and “beaten” in the same sentence tells me we’re missing the point somewhere.

The point is that only when I let go, stop wanting, stop craving, stop desiring, that I’ll stop suffering. Maybe I ought to stop beating myself up.

Easy enough. I’ll quit smoking. And I’ll go on a diet. And I’ll be a vegan. And I’ll donate time to the Big Brothers/Big Sisters. And I’ll do all these good things and I’ll stop all these bad things.

So why do I still feel lousy?

Okay, so not all of it is my “fault.” It’s not my “fault” that Mr. Outsource in Hyderabad mangled his English so bad that now I’m paying for six homeowner’s policies on my one house. That can be fixed. And it’s not my “fault” that the economy’s so bad. And it’s not my “fault” that there’s starvation and death in Darfur. But it sure causes me stress, and the angrier I get at Mr. Outsource, the worse I feel, and the less compassion I can muster. The less the compassion, the less the intimacy, the more the suffering. Mine and others.

Compassion is key. A feeling of intimacy toward the world is key. What compassion and intimacy can I feel if I’m living pretzel logic and every shrug hurts?

No one said this was going to be easy.

It’s certainly simple enough to say, “I’ll quit smoking.” It’s not so easy to do. Man, you crave that cigarette. But you know it’s bad for you, so you persevere. And maybe you quit.

But what about the good things of life, the excellent food at my favorite restaurant, Bow-Thai, in Coral Springs? What about the pleasure of a baseball game on a hot summer’s day with a dirty water chili dog, or a cold beer in a plastic bottle for seven bucks?

Or what about making love to your wife?

All of a sudden, Bow-Thai closed. They did reopen with the same owners and the same cook, so I suppose reincarnation is possible.

And the game was rained out the day my best friend came to town.

And then you caught me making love to your wife.

Suddenly—whoa!—this isn’t so pretty (especially not for me).

How do you quit the good, healthy and helpful habits? Giving up the good things is far harder and just as necessary, as giving up the bad things. Ideas of heaven, of love, of bliss—THROW ‘EM OUT!

Ideas of hellfire, pain, damnation, and Macaulay Culkin?—THROW THEM OUT, TOO!

They’re all attachments. What we fear and what we love are on the same side of that line. We want life to stay the same. We want our parents to be forever young and to love us unconditionally, we always want to be twenty-five and slim, we fight those smile lines with Oils of Delay, we don’t want this movie to end or the Dodgers to leave Brooklyn, or your wife to rat me out (at least I don’t want that to happen). We want things or we want love and we want it the way we want it. We want to stay in our comfort zone, and the problem is that our comfort zone keeps shifting. (Actually, philosophically, we can argue that the comfort zone is fixed and that we’re moving, but I don’t know that it matters.) And even if we don’t mind change, the “Good Old Days” always seem to have been better than the “Right Now Days.” Actually very few of us live in the “Right Now Days.” We usually live in the past—“Remember when?”—or in the future—“When I win the lottery”—and spend only a few moments each day dealing with the here and now. And most of our here and now time is really either anxiety—“I gotta get this done”—or selfish desire—“I wish Mr. Cloggenbrane would shove that clarinet up his nose, when he plays it sounds like a dying wombat.”

Even happiness leads to suffering because it inevitably fades. The girl I love has a bad day and breaks my chops. I get mad. Or upset. Or even sad because she’s having a bad day. I suffer right along with her.

We can’t sustain what we have. Or what we don’t have. We don’t get what we want. And when we get it we don’t want it anymore. The car breaks down, the love breaks our hearts, the dish just breaks. It’s unavoidable. That’s life!

But since life is even more ephemeral than Macaulay Culkin’s career, the only workable way to stop all this wanting and its associated suffering, is to realize that you already have everything you need.

Sounds easy, right? Sure! All it takes is an entire shift in your earthly perspective. All it takes is a constant state of mindfulness. Such a state of mind takes years to develop, and like everything else, it’s impermanent and will come and go.

I don’t know if you can ever totally escape suffering. Why try? Are you more than human? Will the escape from suffering make you less than human? Be careful what you wish for. The desire to escape suffering is like the desire to escape breathing. It’s like any desire really, just another attachment. There is the story of the Zen Master whose son died unexpectedly. When one of the Master’s students found him weeping, the student said one word, “Attachment.” The Master answered, saying, “No, not attached. But still sad.”

If you do manage to let go of suffering even for a moment, suddenly it doesn’t matter so much that I’m not twenty-five because I have only this instant to live. And the next instant, and the next instant, and the next, until I’m instant’d out. What would I do if I only had an instant to live? THINK FAST! ‘Cause it’s already gone.

If I only live in this instant, how can my desires control me? And how can my likes and dislikes define me? I can choose to do or not to do something, I can choose to decide to buy or not buy something, and I can choose how to feel about it or how to act on it. No longer a slave to habits and impulses, I’m also no longer a slave to the thinking I’ve been doing or the things that I’ve been doing. I still think and I still do, but the reality is that it’s all of my choosing.

Too many people, having read Kerouac, are under the impression that Zazen is about stopping your thought process. It isn’t. Zazen is about observing your thought process, watching how the thoughts arise, where they go, how they make you feel, and how they bounce around in your head while they’re there. By taking notice of your thought process during sitting you will learn to do the same thing while you’re working, eating, and, actually, even sleeping (as weird as that seems). When you first sit, the thoughts in your head sound like the primary approach runway at O’Hare. As time passes, the cacophony lessens. After a while, you even learn how to push your own buttons, as in, “He always manages to push my buttons.”

Well, then. Imagine having control of your own buttons! Guess what? If you can push your own buttons that means you can choose how you want to feel or not feel or suffer or not suffer or be attached or not be attached to anything. “Not attached. But still sad.”

Sufferin’ succotash! The irony of the Third Noble Truth is that it is the easiest and the most difficult of all the Four Noble Truths at the same time.

Suffering seems so endemic to who we are, and yet there’s a way around it. We sense it, we know it, we just have to master it.

And that is why we practice . . .

The Fourth Noble Truth: Follow The Yellow Brick Road

The Fourth Noble Truth is not so much of a statement of fact than a statement of intention. In the midst of your perfectly ordinary day of living The First Noble Truth, you decide (as you do a hundred times a day) that you want this or you need that. You want to eat lunch. You need a Number Two pencil. You’re plugged into The Second Noble Truth: “Gimme dat ding.” It’s a song by Dr. Hook, and boy, are you hooked. Having done, to this point in time, just a fraction of the Zazen you will do in your lifetime, you’re still aware enough (just) to realize that you’re doing the hamster on the wheel thing once again. Do you need this? Having decided you don’t (as you do and have done ten thousand times in your life), and more importantly, having decided to do something about it for the five thousandth “once” in your life, what do you do?

The Buddha apparently spent a lot of time thinking about this. After all, he’d come up with this incredible insight into the place of suffering in human nature. Knowing what he knew, he had to figure out a way to actually make it all work. So he called his insights “The Four Noble Truths.” The Fourth Noble Truth is really a road map up and away from suffering. He called it “The Eightfold Path.” (I really don’t know if Shakyamuni called it anything, but his followers codified it all.)

The Eightfold Path is a behavior plan. Think of it as an Eight Step Program to break your addiction to suffering:

To follow “The Eightfold Path” we are asked to always keep in mind our outlook on the world, our intentions, the way we speak and communicate with others, our behavior and actions, how we earn our daily bread, and our effort and attention to how we actually do keep these in mind. It’s an endless circle of capability. It’s also difficult to do. There are so many distractions in daily life, and never more than right now. Losing yourself to work, sex, drugs, the news, an argument with the neighbors, bills, and everything else is the norm. Attentiveness isn’t.

Maybe Shakyamuni never kicked the dog, but you might. Practicing Zen doesn’t suddenly turn a person into a vegetarian pacifist who haunts airport concourses. After a lot of Zazen practice and talks with your Zen teacher you might be able to do the old “Five-Four-Three-Two-One . . . Hold everything!” and catch yourself from having an habitual reaction to something. “Hmmm . . .”

And you might get to the point where you can make sensible decisions about how you’re going to choose to react in a particular set of circumstances.

“The best way to control people is to encourage them to be mischievous.” Suzuki said it. Not me.

And beyond that, at the moment, I’m not even going to pretend I know what I’d be talking about.

Enlightenment?

|

1. Right View |

|

2. Right Intention |

|

3. Right Speech |

|

4. Right Action |

|

5. Right Livelihood |

|

6. Right Effort |

|

7. Right Mindfulness |

|

8. Right Concentration |

adapted from www.thebigpath.com

The Essence of The Four Noble Truths:

“Life isn’t what we want it to be; because it isn’t, we’re unhappy; when we decide it doesn’t have to be, we become happy; and to help us make that decision, we should get plenty of sleep and eat a good breakfast every day.”

Southern Palm Sangha: The First Steps on My Dharma Journey

I joined the Southern Palm Zen Group of Boca Raton in August of 2006.

On April 4, 2007, I (center) received Jukai flanked by my Dharma brothers Jimyo (left) and Shonen (right). Receiving Jukai means that the participant, having vowed to practice the Buddhist Precepts, is permitted to wear the rakusu, a biblike garment symbolic of the Buddha’s patched robe. The cross-hatchings on the rakusu are meant to represent the ordered fields and water channels of the rice fields, wherein frogs, fish, earthworms and insects abide in natural harmony. It’s said that the rakusu was devised during a period of Buddhist persecution as an easily-concealed substitute for the kesa, or full robe. At the time of Jukai, the participant is given a Dharma name. Mine is Konrei, “The Unyielding Spirit.”

In the Jukai Ceremony the Zen student affirms his or her commitment to the Sixteen Bodhisattva Precepts.

These Precepts are traditionally divided into three sets, the “Three Treasures, the “Three Pure Precepts,” and the “Ten Grave Precepts.”.

The Three Treasures are enlightened living, knowledge, and community.

The Three Pure Precepts are abstention from evil, doing good for oneself, and doing good for others.

Many of The Ten Grave Precepts are similar in wording to the more familiar Ten Commandments, though they are considered inspired guidelines for living, not divine commands.

The jukai is encouraged not to kill, not to steal, not to covet, not to bear false witness, not to be ignorant, not to gossip, not to engage in self aggrandizement, to be generous, and to respect the Three Treasures.

Tokudo, my ordination as a Zen monk, took place as scheduled on August 15, 2009, despite my having suffered a broken back as the result of a serious car accident just three weeks before. Although I was in significant pain and had to use a walker to take the traditional steps, my Tokudo ceremony seemed all the deeper for it. Having come face to face with my mortality and the very tenuous hold I have on being a healthy human being, the state of existence represented by being an “Unsui” or “Cloud Water Man” took on a whole new importance. The term Unsui is usually translated into English either as “monk” or “priest;” in a practical sense, there is no difference between the two in Zen Buddhism. An Unsui is a fully ordained clergyman who may give teisho or Dharma teachings, conduct services, and officiate at life cycle rituals. Most Western Unsui generally see theirs as a figurative rather than a literal status.

The term Tokudo itself is one of those wonderfully untranslatable Japanese idioms which means, “Leaving home to take up the journey.” In the days of the Buddha and until quite recently, the Unsui literally did leave home to become a mendicant or a monastic, dedicated to teaching the Dharma. The Unsui did not abandon home and family so much as he (and in those days monks were always males) exchanged one family for another, the Sangha for parents, siblings, spouse and children (if any).

Although a modern Unsui can choose the monastic path, Western Zen has effectively transformed the act of Tokudo into a deeply symbolic ritual in which the Unsui “leaves home” by renewing his or her dedication to the Precepts first adopted in Jukai, and by actively practicing renunciation of fixed concepts, thoughtless habits, and the mindless existence of everyday life. An Unsui is supposed, like a cloud, to move comfortably from moment to moment. Obviously, most Unsui must make an active practice of mindful living; one does not become an Unsui because one has attained anything—rather, Tokudo represents a dedication to an active life of constant practice. It is probably more difficult for a modern, non-cloistered Unsui to keep the Precepts than it was for the Zen monastics of Dogen’s day, the distractions of modern life being all-pervasive. Thus, rededication must go on moment by moment, not just during formal Zazen.

Just as Jukai, Tokudo is very much a service of affirmation in which the Unsui again dedicates himself to the Buddhist Precepts after being ritually purified. As part of the symbolism of purification inherent in Tokudo, the Unsui has his or her head shaved, is given a set of begging bowls, and is permitted to wear the garb of a monk: A long shirtlike garment called a jubon, a belted wrap or kimono, a capacious mantle called a koromo, and a large robe called a kesa. The kesa is a patchy garment, traditionally sewn together from rags of shrouds found at the charnel grounds. The Unsui thus symbolically wastes nothing. With his robes and utensils, the Unsui is a free person: “Just this is enough.”

Although Zen uses basic black and white garments, saffron is a common color in other traditions, not for any reason other than that for hundreds of years corpses in hotter climes were preserved with spices (including saffron) which tended to stain their shrouds yellow-orange, the colors which ultimately became identified with the Buddhist communities of Southeast Asia. Whatever the color or the style of the robes they are all physical representations of the same Bodhisattva Precepts.

I have been asked to describe the difference between Jukai and Tokudo. For me, Jukai represents my personal commitment to the Precepts as practiced locally, while Tokudo represents my personal commitment to the Precepts as practiced globally.

“In going and returning we never leave home.”

Zazen

The Practice Of Selfless Living

Zazen is the timeless practice of realizing our selflessness so that we may be truly of service to others and ourselves. Only in the narrowest sense is Zazen equivalent to Shikantaza or “just sitting” as a form of meditation practice. When Zazen becomes an integral part of your life Zazen is expressed in every action you take.

Here are the Southern Palm Zen Group’s guidelines for sitting Zazen

1. Sit on the forward third of your chair or on a cushion on the floor.

- Arrange your legs in a position you can maintain comfortably 3. Straighten and extend your spine, keeping it naturally upright,

centering your balance in the lower abdomen. 4. Keep your shoulders straight and chest open. 5. Tuck your chin in slightly, keeping your head upright, not leaning forward, backwards, nor to the side.

6. Keep your eyes lowered to a 45 degree angle, neither fully opened

nor closed, “softly gazing” about 3 feet in front of you.

7. Keep your lips and teeth closed with the tip of the tongue touching

the back of the upper teeth.

8. Place your hands on your lap with the right palm up against the

abdomen, and your left hand (palm up) resting on your right hand,

thumbs touching lightly, forming an oval (the “cosmic mudra.”)

9. Take a deep breath, exhale fully, and then take another deep breath.

Then let your breath settle into a natural rhythm.

10. Remain as still as possible, following your breath and return to it whenever thoughts arise.

11. Practice daily at least 15 minutes or more.

My Thoughts on Zazen

Zazen is the central practice of Zen and is the primary, but not exclusive, method for meditation. Although Dogen Zenji recommends the lotus posture and the use of a zafu and zabuton for Zazen, none of these three are mandatory. The point is to sit, and whether you or I use the traditional postures and implements or whether we sit on the throne of the British Empire (or any other throne) is less important than just sitting.

It’s impossible to stop our thoughts. They’re going to pop up and disappear about as ephemerally as bubbles in a pot of boiling water. The point is not to stop this from happening. Instead, just let them come and go—Pop pop pop! If you want to, consider where your thoughts come from and go to, and then consider just who is doing the considering. Before long, you’ll be looking at the back of your own head, so to speak.

Watching the breath is a technique that’s useful to allow the practitioner to minimize distractions. Shunryu Suzuki calls these distractions “mind weeds” and “mind waves” and actually credits them as a method of deepening our practice. The more we sit, the less we’ll be distracted by these random thoughts. Don’t expect that they’ll ever stop forever. Breath counting helps us to redirect our wandering attention, yes, but the point of Zazen is not mastery of the ability to count to ten over and over without interruption. Breath counting is only a technique—it is not Zazen.

Zazen isn’t sleep or sleepiness, either. At those times when I attain what I presume is samadhi, my “monkey mind” stills, my random thoughts become few and far between and less memorable, and I rest my tired and hyperactive frontal lobe. But whenever I anticipate that this is going to be the outcome of Zazen it isn’t.

That tells me something.

For More . . .

Please Go On To Our Other Dharma Pages

The Links Are Below

(Under Construction)

THIS PAGE IS UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Go Home To The National Special Needs Network